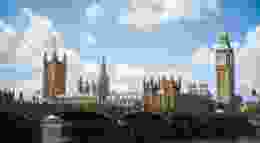

We need to get real on a ‘no’ deal

A 'no' deal is looking increasingly likely. Whitehall must stop its endless undermining of a 'no' deal and instead focus its energy on the real opponent that lies ahead, explains Lee Rotherham.

That being so, it behoves Whitehall not only to plan heavily for the true Brexit backstop; but to stop briefing the press that No Deal is worse than any Bad Deal that it anticipates it will ultimately sign. That means discarding the Remainer mythology of what lies in the default.

It is rather a short sighted approach to anticipate a looming disaster, and prep for making it look better by blowing up your defences. Slighting the walls emboldens the opposition, and makes calamity in the field itself more likely.

Sometimes it does seem as if the Brexit Project Fear output is coming from some sort of psychological test. That there are people in white lab coats with clipboards ordering people to keep cranking up the dial, in a kind of modern day media Milgram Experiment.

If so, the findings when they get published will be extraordinary. Some of the Project Fear stories are so spectacular they would daunt Lucasfilm.

Take the example of medicines, where it was casually mooted that in a No Deal scenario the country would run out of insulin. That ignored the prospect of UK authorities unilaterally recognising current certification processes as still transitionally authoritative. Then on review it transpired the trade was more complex and global. This pantomime was further exposed when AstraZeneca reportedly warned that if the Commission did get obstreperous about medicines, it would no longer be able to guarantee the supply of its products to patients in the EU who are suffering from cancer, heart and lung problems. So much for that scare story.

The reason why so many of these scenarios are implausible is because they are predicated upon a false baseline. As such, the prediction is simply a Tarot call. This has left the two sides in the Brexit debate in aphasia from the outset, since their very starting premises are disjointed. It's like discussing border policy where one side is talking about the 38th parallel, and the other about the 49th.

I explore the fundamentals in a new paper (click here). Hopefully it may encourage greater clarity to emerge, though given the concepts I fear I may have done little more than translate cuneiform into hieroglyphs.

At its simplest, Doomsday Remainers envisage the UK as having no viable alternative to deep association with EU systems. As a result, they would be prepared to sign up to any deal rather than pursue a much looser approach – especially if they can deliver a simulacrum of the UK's current EU membership.

However, the landscape of WTO default as they portray it can only be delivered if negotiators manage to escalate mutual frustration into a major trade war. The reality is that there are a number of variables generating additional building blocks even in the worst case scenario. Importantly, these are accompanied by precedent, meaning that they cannot all be lightly be dismissed by the Commission for being in breach of Single Market preconditions.

The first variable is with the EU's own international agreements. Mega-pessimists say that a WTO default doesn't work, because countries like the United States and Australia don't just trade with the EU on WTO terms, but also have several dozen additional bilaterals. But that is the precise point in play. A No Deal setting can be expanded upon by replicating these very arrangements. Incidentally, around half of these agreements are actually agreed through multilaterals, so in many cases the UK can just sign up. At a stroke, the fall back No Deal becomes a 'WTO+'.

That of course does still leave gaps. The strategy of DExEU and, until recently, the Cabinet Office has been to strive to maximise the number of mutual recognition arrangements that would fill these. The point was made in the Prime Minister's Mansion House speech, where Theresa May said,

"In particular we will want to make sure our regulators continue to work together; as they do with regulators internationally. This will be essential for everything from getting new drugs to patients quickly to maintaining financial stability. We start from the place where our regulators already have deep and long-standing relationships. So the task is maintaining that trust; not building it in the first place."

This quote was not a not secluded ambition, and runs as a thread through the Road to Brexit speeches (click here). Of course, much here depends on the willingness of the Commission to pursue such bilateralism. Much rests on its readiness to recognise that exceptionality of the UK, beginning from the starting point of full compliance with Single Market requirements, including testing and certification. It would be an error to assume, particularly given the ticking clock, that a wide-ranging prospect here is now deliverable. However, there remain a number of uncontroversial areas where administrative elements could be established, new requirements simplified, or equivalence in narrow sectors signed off.

Both these prospects already take us away from the vanilla WTO default. It has been suggested by Brexit-Breakers that the UK will have a rum time with everything from airplanes to x-ray machine components. In practice though, quick fixes and new micro arrangements across the panoply of 35 'de-accession chapters' are deployable. The reality of what can be bilaterally cobbled together from a No Deal scenario turns out to be more like a sliding scale.

It is also still possible, though increasingly a challenge, that a last minute package might be predicated not on WTO terms but on an existing wider agreement. Our paper lists no fewer than 29 of the EU's 42 trade models that could be dusted down late in the day to cover gaps. A number of these are not viable baselines, since for example they manage customs unions or are asymmetric treaties, but do still contain permissive clauses that may be of value. But of particular note are the examples of Canada's Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement; South Korea's Free Trade Agreement; and Japan's Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA).

Or again, while inferior, we might cite the example of CEFTA, the Central European Free Trade Agreement. This model was created as a staging post for countries transitioning to join the EU; it is equally plausible that the concept could be deployed for a nation that is departing. It's another precedent with notable implications that has been peculiarly absent from the public debate. [http://cefta.int/]

And separately we might also cite the examples of East Germany, Algeria and Cyprus, where the European Commission went along with plans that simply buckled the rules. [http://www.theredcell.co.uk/uploads/9/6/4/0/96409902/brexits_dreary_steeples.pdf] In turn, bolt onto these those additional bilaterals we raised earlier, and you are on the verge of delivering 'Canada+'.

The Project Fear false narrative reads like the utterings of a Doomsday Cult. But, while occasionally comedic, it is damaging. It is distracting us from the many areas that both public and private sectors genuinely need to plan and prep around.

We are pragmatic, and cautious, and chary about what will follow from a break down in discussions over the Chequers proposals. A WTO+, WTO++, FTA+ or even (that increasingly vanishing prospect) a SuperCanada deal still leaves areas of transition and gaps. One can predict no less, given that we are leaving a complex federal superstate in the making. These problems should not divert us from our purpose.

Given the Commission's track record, it is highly likely that demands will now be made of the UK that not just further stretch but completely snap the British red lines. Downing Street will be forced to either accept terrible terms forced on them, or to say No.

That being so, it behoves Whitehall not only to plan heavily for the true Brexit backstop; but to stop briefing the press that No Deal is worse than any Bad Deal that it anticipates it will ultimately sign. That means discarding the Remainer mythology of what lies in the default.

It is rather a short sighted approach to anticipate a looming disaster, and prep for making it look better by blowing up your defences. Slighting the walls emboldens the opposition, and makes calamity in the field itself more likely.

To risk a crass analogy, if you shell the Schutzbund, you end up with Anschluss. No surer way exists to deliver total defeat than to target one's own reserves.