There's a toxic cocktail of chemicals in our rivers

The threat to human and environmental health from pesticides, pharmaceuticals, plastics and other pollutants is an issue that I return to in the House of Lords again and again.

It's an issue that rising up the public agenda, with two major reports in the UK and Europe last month, drawing attention to our growing understanding of cocktail effects - the impact of mixtures of toxins to which we are exposed to, often on a daily basis.

There’s also increasing concern about the effects of metals, particularly heavy metals in the environment, with recent discoveries showing how they can - through co-selection - produce antibiotic resistance.

Analysis by The Rivers Trust and Wildlife & Countryside Link shows that mixtures of “four toxic forever chemicals, the pesticide 2,4-D and the commonly used painkiller ibuprofen” were identified at over 54% of sites studied by the Environment Agency.

While pesticides are purposefully applied, the other chemicals listed are unintended contaminants from a range of sources. Given the backdrop of near-constant sewage discharges into our waterways, and the high rate of consumption of medicines as a stopgap solution for a profoundly unhealthy society, contamination by pharmaceuticals is unsurprising.

But the problem extends beyond painkillers and pesticides: yet another analysis by The Rivers Trust points out that 0% of rivers met good chemical status in 2019.

In the same week in the European Union, CHEM Trust produced a similar report, highlighting how current rules “assess chemicals in isolation, one by one, and within regulatory silos” and so “vastly underestimates the true, real-life risk on our health and the environment resulting from combined exposure to multiple chemicals”.

So how can the government remedy this? As a recent policy briefing by UK Youth for Nature and Wildlife & Countryside Link highlights, the UK’s upcoming Chemicals Strategy provides an excellent opportunity. Its publication forms part of the UK’s five pillars for reducing pollution as set out in the 25 Year Environment Plan.

To craft a Chemicals Strategy that is fit for purpose, the government can draw on the incredible wealth of resources provided by the third sector: charities and learned societies have banded together to put forward their 12 key asks - simple recommendations with the potential for powerful ramifications.

These include key ask five: moving to a “default approach of assessing and regulating substances in groups”, so that one banned substance is not replaced by a very (chemically) similar one, and so ad nauseam.

I often cite the 2022 paper by Persson et al. which showed that we have exceeded planetary boundaries for novel chemical entities “since annual production and releases are increasing at a pace that outstrips the global capacity for assessment and monitoring”. This doesn’t have to continue being the case.

By both increasing the capacity for assessment and monitoring and reducing the production and release of pollutants, the UK Government can play its part in bringing humanity back into a safe operating space.

The former can be achieved through dedicated funding and recruitment of scientists, and intelligent monitoring - for example in groups as stated in key ask five; the latter is a simple matter of regulation, as outlined in key ask two, forcing producers to employ less hazardous chemicals in their manufacturing processes if they wish to access the UK market.

The UK Government has made, and broken, many promises when it comes to environmental regulation. It behoves the executive to ensure that its Chemicals Strategy is aligned with the demands from organisations with our wellbeing in mind, like Breast Cancer UK and the Wildlife Trusts.

Civil society organisations have spoken out to protect people and the environment; will the government listen?

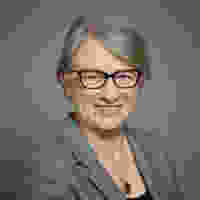

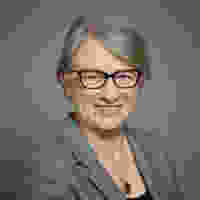

Baroness Natalie Bennett writes alongside Senior Policy Researcher, Dr Paul-Enguerrand Fady.

Baroness Natalie Bennett is a member of the House of Lords and led the Green Party from 2012-2016.