We are abandoning the children of our carers

When I spoke with a group of women holding essential UK services together - nurses, social workers, carers for the elderly and (a number of them) carers for disabled children and young people – they were in a state of acute distress.

The distress was not about their work, which they knew was meaningful and important, but about their treatment by the Home Office. For they are also single mothers, with children ranging in age from 16 months to 16, for which they have sole parental responsibility. Among the group are also some single fathers.

Their children are in Zimbabwe, in Guyana, Western and East African nations and other Global South nations, often in dangerous, unstable situations.

One mother spoke of how she had temporarily left her children in the care of her parents, their grandparents. Initially in 2022, while her mother had lost a leg to diabetes, her father was healthy and able to cope. But then in 2023 he suffered a severe stroke, and now her early teen daughter is the carer for both of her grandparents, and her seven-year-old brother.

Another left her early teen daughter in the care of her then 22-year-old sister, with the expectation the arrangement would only last a few months. Now, her sister wants to move on with her life, and the daughter has no one to care for her.

One mother has two children with her here in the UK, but the third was refused a visa, and has been moving every few months to stay with a different family friend. Understandably, he is profoundly unsettled.

Another in desperation has put her son into a boarding school, but the situation is financially unsustainable.

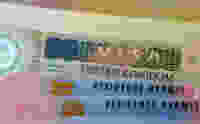

All of them have been separated from their children by the Home Office. They, legally and properly, obtained visas to work in the UK, with the understanding their children would be able to join them.

Now, they are trapped: “I’ve had four refusals. I’ve had five or six, I’ve lost track now.” “I have had two.”

Again and again, they have thought they had assembled the appropriate paperwork, then were told, most often, that a Home Office official “did not believe” they had sole responsibility for the child.

“Couldn’t the father look after the child?” No. The stories are different, but the answer obviously the same. “We never lived together.” “He took another wife, and they live in a community that practices female genital mutilation.” “He has never had anything to do with the child.”

Story after story speaks of the Home Office as failing to understand the social norms of the societies from which we are drawing these essential workers. Many have only got a court order for custody when the British Government demanded it, then the timing is held against their case.

But that is because in many cases the social norm is that the mother is the one responsible for children; that was never in question in their home country, so no need to go to court, until the British state questioned an arrangement for which there is already bountiful evidence: financial statements, school records and more.

Sometimes children are treated differently depending on whether they have their mother or father’s surname. But that ignores the way in which single parenthood remains stigmatised in some societies, and the challenges a mother might face if her child has no acknowledged father.

With many of these horrifying accounts of encounters with officialdom starting under the former Conservative Government, there might be little surprise that the problems arose. With its brandishing of the hostile environment as a culture wars political weapon, Home Office officials may have been influenced by their political masters, rather than the law.

But now, months into a new Labour government, hopes are fading that justice, compassion and the rule of law – the contract we made with these essential workers when they ripped up their lives to come to care in our community – would return. The workers all agree they have seen no difference in the Home Office stance, or attitude.

“We feel cheated.” “We feel lied to.” “They are destroying our children.”

I will be raising this situation with ministers, asking them to meet with the parents affected to understand first-hand the dreadful circumstances the Home Office has left these workers in. I hope that might make a difference.

Also, I will be highlighting the fact that no more parents will be put into this – exact – situation, because from March 11, the rules were changed and most care workers will not be allowed to bring their children to the UK with them, no matter what their circumstances. Those are the rules they have arrived under.

For what right do we have to tear families apart? With desperate circumstances arising from war and internal conflict, from the climate emergency, from the legacies of colonialism, many want to – and need to – offer their labour. Should we be demanding that they separate from their children, sometimes leaving them parentless? And what will we do if the children were in stable circumstances that then break down? Will we care for the children of the carers?

The discussion with the workers was arranged by Women of Zimbabwe project, part of the Care for Someone charity.

Baroness Natalie Bennett is a member of the House of Lords and led the Green Party from 2012-2016.