Why can't Theresa May learn from her mistakes?

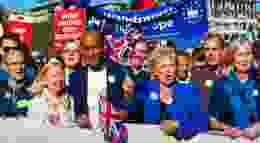

Despite seeing the crippling effect the 'Dementia Tax' had on her electoral prospects at the last election, Theresa May continues to generate yet more punitive, vote-losing proposals on social policy, says Bruce Newsome.

Theresa May reached the top of British politics despite her avoiding key decisions in most areas and repeating the same mistakes in others; at the root of all her political problems is a curious inability to learn from those mistakes.

Her inability to learn explains her indecisiveness, and her indecisiveness explains that comment by her former Cabinet colleague Ken Clarke that she is "a bloody difficult woman." Clarke said it when May became prime minister in July 2016 – he said it then as a warning about her procrastination. Since then, she has repeatedly misappropriated the quote as a boast about her negotiating skills with the EU – I pause for ironic laughter.

On Brexit, her current acutest mistake is to keep proposing that Britain should remain in the European customs union: even though the European Union has reiterated that the customs union cannot be unbundled from all EU principles – including the free movement of peoples, which May has said must end if Brexit is to be meaningful. The EU has reiterated also that membership of the customs union means membership of the single market, which would not allow Britain to reach independent deals on trade with the rest of the world, which May has said she wants to achieve. So many contradictions – more amazing is that she keeps repeating them.

Her foreign secretary (Boris Johnson) was moved to criticize her proposal publicly, frustrated by weeks of private avoidance. Incredibly, May told Cabinet that she would not drop the proposal, nor did she did confront Johnson. Why? She doesn't have the political sense to judge even her Cabinet colleagues, despite weeks of reports on their horror. An unnamed cabinet minister told ConservativeHome that she grossly over-estimates her supporters in Cabinet, that her proposal would please nobody, and that she should give up the customs union entirely. Even the long-loyal ConservativeHome's editorial is warning of May's procrastination on Brexit, while The Daily Telegraph and The Sun newspapers repeated their pleas for decisiveness.

Her procrastination is self-fulfilling. She delays in policy, then she justifies more delay because her government is unready in practice. This same week, civil servants told the Cabinet's sub-committee on Brexit that Britain's borders may not be ready before 2023 – that would be seven years since the referendum, four years since her fake "separation" from the EU in 2019. Don't let her fool you that borders are just that complicated – no, they're not; they just need the appropriate practices, technologies, and personnel, all of which are on the shelf; but no orders have been made.

The unreadiness is caused by lack of clarity in policy, not anything material. In the same week, the Public Account Committee slammed departments of government for lacking plans for life after the EU. One of those departments deals with the environment and food (DEFRA) and thence fishing: it's not helped by May's administration, which has secretly conceded the EU's continued right to fish in British waters, drafted the legislation, and issued licenses to foreign companies for periods beyond May's fake separation from the EU in 2019, without publishing any policy on the quotas or schedules.

Her procrastination gives time for more opposition to build, more diversions, more project fear. For instance, this week the Liberal Democrat Lord Teverson – fresh from rallying countless defeats in the House of Lords of the government's bills on Brexit – posted a warning that Britain's food would rot at the border without the customs union. That makes him this week's barmy Brexit-basher, shamelessly pretending that the EU invented trade.

May cannot learn any better on domestic policies than foreign policies. She's never had anything substantive to say about Conservatism beyond sitting on the fence between consensus and self-deprecation, and she's never learned that voters need something to vote for, not just vote against. May's first speech as chairwoman of the Conservative Party back in 2002 told delegates that they were "the nasty party" and represented too narrow a demographic. She never offered a Conservative vision then, or even in 2017, when – as prime minister – she called an unnecessarily early general election, and lost David Cameron's clear majority.

The local elections last week confirmed that she has earned no more support since the general election of 2017, despite the Labour Party digging itself even deeper into chaotic retro-socialism. Her repeated mistake is to avoid a compelling conservative vision – she just keeps telling voters that she's not as bad as Jeremy Corbyn. After the elections, she posted on ConservativeHome her triumphalism that the results were not as bad as had been forecast; she credited local councillors; she did not credit herself; she did not even mention conservatism; her only hint at differentiation from the opposition is that "our party" is less "ideological' and more "practical." "We know that while political differences may separate us, so much more unites us and we can all achieve more by working constructively together." She sounds like one of those left-wing reductionists who thinks that all problems in the world are due to "divisiveness". She would look great as one of those school heads who is always bleating about "community" – but as leader of the Conservative Party she should be clarifying to voters what is wrong with reductionism, not aping the reductionists.

She's no better at the cut-and-thrust of politics in the House of Commons. She cannot seem to get the better of the stumbling, slurring Corbyn in Prime Minister's Questions – the main event of her week. As one sketch-writer pointed out: when Corbyn asks her to clarify her proposal on the customs union, "May's plan seems to be to agree with no one but to avoid saying that she does not agree."

Then her lackeys keep generating the same vote-losing proposals on social policy. The most ridiculed policy of her campaign for the general election in May 2017 was to propose to seize the assets of the elderly for their terminal care – those persons would have paid already through income tax; for most of them their biggest asset would be their home, which would have been taxed separately through local rates and other property taxes. The proposal was nicknamed the "dementia tax" for its penalization of the elderly, but the injustices were wider. People without assets would still get their care for free, so where is the incentive to own a home or accumulate legacies or even to work? What's the point of a contribution-based system that taxes your means? What gives a government the right to seize assets at all? The proposal was rife with injustices and disincentives to work – from a Conservative government! But May cannot learn: this week, reports emerged that her administration is considering imposing national insurance (effectively a 12 per cent income tax) on working pensioners to pay for their care: same injustices, same shunt to the left-wing consensus, same rejection of conservative values.

When will May ever learn?