Petrochemical overproduction is damaging the recycled plastics market

Recycling is a poor third on the waste pyramid, after “reduce” and “reuse”, but it is certainly better than the discarding of destructively produced materials, particularly when it comes to plastics, on this planet that we have choked with the almost indestructible, pernicious pollutant, at great threat to our own and environmental health.

That’s evident with metronomically regular reports now of the pernicious spread of microplastics – in the air we breathe (we inhale a credit-card’s worth every week), in all types of food, and in our own blood, breast milk, placentas and probably, brains.

So where is this pollution all coming from? Let’s start at the beginning.

Petrochemicals are chemical compounds derived from petroleum or natural gas. They are used for a range of products, including plastic goods and packaging.

With all the worrying news about microplastics, it might surprise you to know there was a notable increase in the production of petrochemicals in 2023, particularly in China and the US. Last year, the production of ethylene – one of the most commonly used petrochemicals – increased by 42mn tonnes compared with the amount produced in 2019.

That’s why I’ve put down an oral question in the House of Lords today (Tuesday) to ask the government’s perspective on this, particularly in light of the fact that the increase in production has so far outpaced demand.

Ethylene demand only reached a third of the total amount produced last year. This surplus has made these chemicals cheaper, meaning that the virgin plastic they are used to create is now less expensive than recycled plastic. In turn, recycled plastic has increased in cost due to rising demand as businesses have tried to use it to lower their carbon footprint in line with new regulations and consumer interest.

The Financial Times reports that this will cause businesses to revert to using virgin plastics. Moreover, the petrochemical production process itself is damaging to the environment.

What is the impact of this increase?

The surge in virgin plastic means even more plastic waste will be added to landfills. The world already produces twice as much plastic waste as it did twenty years ago, with waste expected to increase threefold by 2030. Already in the UK, a quarter of all plastic waste is sent to landfills, a considerable proportion of which are single-use plastics. A significant part ends up exported to the Global South, theoretically for recycling, but frequently not recycled.

Little is known about the long-term health impacts of microplastics, though lab tests show that they damage human cells and microplastics in plastic water bottles have been linked to cancer, weight gain, insulin disorders, and reproductive issues.

The ultimate aim is to establish a circular system, where new plastics are minimised and existing ones are recycled. However, we are clearly heading in the opposite direction. Moreover, while the process of recycling plastic is not without risk, especially concerning the release of microplastics in the absence of adequate monitoring, studies have shown that recycling is significantly less damaging to the environment than creating new plastics.

Petrochemical manufacturing also requires a significant proportion of the world’s oil and natural gas. With petrochemical demands expected to increase, the International Energy Agency predicts that a third of the growth in global oil demand will be needed for petrochemicals by 2030 and close to half by 2050.

When this oil is converted to petrochemicals it leads to a considerable amount of greenhouse gases being released into the atmosphere. Major oil companies like ExxonMobil have invested billions in expanding the petrochemical industry in recent years, making it difficult to see how ambitions to reach net-zero by 2050 can be achieved.

This comes at a time where global crises have shown how precarious our reliance on oil is and how changes to its supply chain can have considerable effects on ordinary people. Oil suppliers have also been implicated in actively funding wars, including by supporting the Russian armed forces in their invasion of Ukraine and providing funds to Azerbaijan’s military in Nagorno-Karabakh, resulting in the displacement of ethnic Armenians from the area.

What needs to be done?

We must act rapidly to curb the overproduction of petrochemicals and prevent the creation of new plastic. Often, the ordinary consumers are told that they have the ability to turn the tide. Of course, there are choices we can make as ordinary consumers to prevent our use of unnecessary plastics, like opting for reusable items to reduce plastic waste.

However, individual actions can only go so far and in fact, most consumers in the UK and US have been shown to prefer sustainable products that do not contain single-use plastic. Unfortunately, there is little the individual consumer can do if retailers continue using single-use plastic and multi-billion corporations continue to use virgin rather than recycled plastics because these industries prioritise profit and investment over preservation of our world.

Just 20 companies are responsible for producing more than 50% of global plastic. Governments must target these corporations and make them work towards ending plastic use, and at the very least ensuring all of their use is of recycled plastic. Some governments have already taken steps in this direction – EU states have drafted legislation requiring beauty companies to spend 80% more than they currently do to remove microplastic waste in waterways.

Governments also need to continue initiatives to properly manage plastic waste, including by assisting individuals to recycle more efficiently. Nine of Europe’s member states send less than 10% of plastic to landfills. More can be done, and PlasticsEurope calls for a landfill ban on any post-consumer waste by 2025, creating recovery-focused collections. They also argue for extra collections for any packaging – that’s the “producer pays” responsibility the UK government claims to support.

This article was written alongside King’s College London intern, Jennifer Howe.

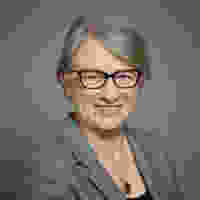

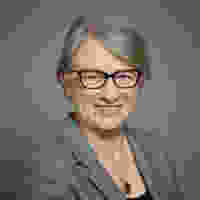

Baroness Natalie Bennett is a member of the House of Lords and led the Green Party from 2012-2016.