Up close and personal with a farcical Brexit debate

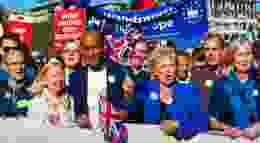

With a panel that counted Michael Gove and Lord Adonis among its ranks, Bruce Newsome discusses Chalke Valley history festival's Brexit debate and who was left standing once the dust had settled.

When a history festival organizes a debate on "Brexit," it frames a historical question ("In the light of its past, is Britain ready?"). While the panellists diligently referred to history, they never addressed whether Britain is ready. Indeed, the debate grew more divisive and ultimately ended in farce. Along the way, panel and audience illustrated Britain's increasing divide on everything from epistemology to etiquette.

The debate pitted two Brexiteers against two Remainers, all familiar with each other, but unaffectionate, resigned, and glum from the start.

Michael Gove (the Environment Secretary and sudden favourite for next leader of the Conservative Party amongst rank-and-file) and Robert Tombs (professor of French history at Cambridge) both welcomed Brexit as evidence for confidence in British history, institutions, and trade with the world outside the EU.

By contrast, Lord Adonis (a former Labour minister) and Afua Hirsch (a journalist for The Guardian) both characterized Brexit as a reversion to the worst aspects of Britain's past – insularity, imperialism, racism, and belligerency.

While Gove and Tombs explained Brexiteers as repelled by the EU's incompetence, Adonis and Hirsch interpreted Brexiteers as misguided by poverty, xenophobia, and nostalgia.

From the start, most of these disagreements turned on irreconcilable biases. Tombs was invited to give the opening statement and chose to focus on the long-term stability of British institutions despite the EU's tumultuous development, and the strength of the British economy despite the declining economic importance of the EU. Tombs gave the best elucidation of the day: "The referendum was a vote of confidence in our institutions, even though it was a vote of no confidence in the people running them."

It was downhill from here.

Afua Hirsch was chosen to follow, immediately switching to "narratives" – but if everything is a narrative then nothing is truth. Her narratives are self-selected, subjective interpretations – framed as counters to myths or prejudices, but reducing to myths and prejudices. She claimed that Britons don't have a narrative about how the Empire created Britain's multiculturalism, but we do – we have a history (many books are titled in effect "from Empire to multiculturalism"). She wanted to counter the "myth" that Britain was not "intimately linked with Europe" before the Empire, but there is no such myth, except as peddled by Remainers who pretend that the EU invented trade and peace. In a later statement, she would complain of a "false narrative of sovereignty", a "mythical illusion that we the people decide everything for ourselves."

Hirsch's justification for starting on Empire remained vague, until she made her prejudices explicit: she held self-evident that Brexiteers were driven by "nostalgia" for Empire: the "history of Empire is not our future", she continued; the Commonwealth cannot supply what the EU does. Moreover, Britain owes the Commonwealth for its imperial injustices. In a later statement, she said that the Commonwealth sends more "wealth" (whatever that means) to Britain than Britain returns in aid. If that is her standard of exploitation, then almost all 53 members of the Commonwealth must be a victim of Britain. At times, she seemed to think this was a debate on reparations.

Strangely, the chairman's order of opening statements followed Remainer with Remainer. Adonis set out as he would finish: self-promoting and insulting. He promoted his book, then joked that he was holding a copy for Gove to tear up (the previous day, reports emerged that Gove had ripped up a report on Theresa May's plan for a new customs relationship). Gove looked non-plussed and impatient.

Adonis then insulted Jacob Rees-Mogg, who wasn't there and had never mentioned Adonis during his own talk the previous evening; indeed, Rees-Mogg had pleaded for politicians to "avoid personal attacks on each other." Adonis clumsily reprised France's loan of the Bayeux Tapestry, then said that the Queen is exchanging Jacob Rees-Mogg, "who is much older." A large minority of the audience laughed.

Then Adonis turned on Nigel Farage's children for holding German passports (through their mother); the attempted joke was that Remainers should get their children adopted by Farage.

Adonis' delivery was excruciatingly clumsy as well as unseemly. He huffed and mumbled, jerked and twisted, from one incomplete sentence to another, until he got to the punchline, like an inexperienced teacher who wants to be matey.

When Adonis finally got to an argument against Brexit, the delivery did not improve much. Adonis referred to his book against Brexit, which has been damned already, but he scattered its fallacies and misrepresentations without revision (such as: Brexiteers were driven by declining wages; the "right-wing of the Conservative Party is scapegoating foreigners").

Adonis invented yet more myths: EU regulations, he said, are not threats to sovereignty, they are "expressions of sovereignty"; Britain has not surrendered sovereignty, it signed up "freely." Adonis said that membership was even more important given the rising importance of European trade (this is not true), Russian threats, and American belligerency.

Adonis rambled on. Gove raised his eyes to the chairman, who reflected the same but did not intervene.

Gove finally got his chance. He pointed out that the majority of Britain's history has been outside of European integration, during which Britain led the world in political, artistic, and scientific development. Like Rees-Mogg the previous day, Gove pointed out the incompatibility between Britain's tradition of national accountability and the European integrationist's pooling of sovereignty. The EU, he said, is like any empire, offering pooled resources, but also declining accountability and endeavour. Gove pointed out that Britain has become more tolerant and confident, while continentals are stuck between integrationists and populists, nationalists, and nativists.

Gove refuted Adonis' claim that the EU brought peace – it messed up its leadership of the peace operation in the former Yugoslavia (it was succeeded by NATO). Tombs would follow up by attributing European peace to democratization, while the EU is "undermining democracy" by "incompetent" and "centralizing authority."

Hirsch and Adonis retrenched with ego-centric anecdotes. Both Hirsch and Adonis separate themselves as children of immigrants, victims of prejudices and everything else negative that they think characterize our past. They don't seem to realize that their self-separation is prejudicial: they repeatedly infer that people unlike them can't understand what they understand. They don't like Britain's past and they're not resolved to Britain's present. Like fashionable thinkers of the 1930s, their hope for Britain is continental.

Hirsch and Adonis are Britain's accusers and the EU's denialists and apologists. Adonis' opening statement included the plea not to change anything when everything is alright, but Tombs replied that things aren't alright. Hirsch jumped in: "I really object to this notion that the EU is an empire," but talked about her personal relationship with the EU. Adonis declared "nothing imperial about the European Union – it's a club of democracies" that don't want to leave.

Over several rounds of exchanges, too much time was wasted on Adonis' ridiculous analogy from the EU to NATO. Gove pointed out that the former is a confederation, the latter is an alliance, but Adonis continued to assert that the alliance's commitment by all to defend any is akin to a surrender of sovereignty.

The more ridiculous the linkages, the more the audience got riled up around markers of bipolar politics. Adonis received his biggest cheer when he complained about the "austerity" that only the EU could fix. Gove's biggest cheer came when he said that centralization is not "pragmatic," as Adonis had claimed, but ideological. Hirsch's biggest cheer greeted her concluding appeal for a Britain of "fairness." Tombs was appreciated most for his reprisal of the strength of Britain's relationships when sovereign. Few of the 750 seats (at £14.50 each) seemed undecided or open-minded. At one point, the chairman observed that the audience seemed evenly split – nobody demurred.

After an hour of ill-disciplined debate, the organizers had budgeted for 15 minutes of audience questions, when chaos really broke out. Adonis was most responsible: he became ever ruder and more domineering. He interrupted Gove's reprise of Britain's democratic institutions to claim that Britons had rediscovered their democracy only "in the last two or three years," prompting the first boos. When he repeated his demand for a second referendum, several shouts rang out to the effect that we have voted already.

The audience had decided they were at a pre-election husting. The chairman made his only attempt to cut in, but Adonis cut him off by declaring that he would finish his "allowable minute" – by then, Adonis had been speaking several minutes contiguously.

Professor Tombs was given the last comment, because an outstanding question from the audience had been directed at him, but Adonis interrupted with questions of his own, while Tombs – still looking at the audience – waited for quiet and even raised his hands to signal "T" for "time out."

Indeed, time had run out, said the chairman, but Adonis interrupted him too, to ask the audience for a snap poll on whether they would vote to remain in the EU if Theresa May agreed something that he mumbled. Even I – in the front section – could not understand what he specified. He quickly asked the audience to raise their hands for, then against, at which point shouts emerged of "What was the question?" Adonis paused for a few seconds, then declared that most people had voted to remain; he was again received with howls of derision, while the audience streamed out into the humid afternoon.

A stranger was already on stage to tell the audience how to buy the panelists' books; Gove, who had no book to sell, remained glummest.