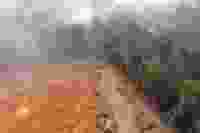

Tropical forest countries cannot shoulder the whole burden for ending deforestation

After a pledge to end deforestation by 2030 was announced last week at COP26, Stephanie Wray writes that simply asking countries to police deforestation won't work; consumers need to stop buying the products of deforestation if any progress is to be made.

No sooner was the COP26 pledge to end deforestation by 2030 agreed than concerns began to be voiced. In particular, it was pointed out that deforestation has actually increased since the New York Declaration on Forests in 2014.

Speculation began on how such a pledge might be enforced. Would it be possible to verify that forests were actually being protected by using satellite images? Could the national sovereignty of tropical forest countries – including Brazil, Argentina, Indonesia, Malaysia, Ghana and Cote d'Ivoire – be in some way challenged in they failed to stop deforestation as pledged? And, if so, what enforcement mechanisms could be used?

But we really need to look more closely at why many tropical forest countries have failed to honour past commitments to halt deforestation. Many of the countries in question only have partial national control over deforestation within their own borders. Regional bodies can have weaker deforestation laws and local enforcement can be poor.

For example, two multilateral zero deforestation agreements, the 2006 Soy Moratorium and the 2009 Brazilian Federal Prosecutor's TAC's have been linked to significant reductions in Amazon deforestation. But they were counteracted by major increases in deforestation and native vegetation loss in the neighbouring Cerrado savannah region.

We're looking for solutions in the wrong place. It's not necessary to somehow compel tropical forest countries to enforce their international commitments. Regions within tropical forest countries are not cutting down their trees for the fun of it. They're doing so because demand from the West for the commodities produced through deforestation is high. Deforestation is not random. The vast majority of it takes place to produce only eight commodities: beef, leather, soy, palm oil, cocoa, timber, pulp and paper, and rubber.

This means that it lies in the power of developed Western countries to move the needle on deforestation globally. If the West stopped importing these commodities from countries where we know that deforestation is an issue, we could massively slow deforestation at a global level.

It may not be in our power to police Brazil. But it is in our power to eliminate forest risk commodities from our supply chains. We could stop eating South American beef and dairy, which would in turn reduce demand for the soy that feeds the cows. We could stop wearing South American leather. We could eradicate Indonesian palm oil from a host of consumer products and source our timber and paper from sustainable forests in northern Europe.

According to JNCC data, if the global market for beef shifted to avoid all production involving deforestation, then over 2 million hectares per year would be saved; that's around 25 per cent of global forest loss. Another 9 per cent would be saved if soy and palm oil were also produced sustainably.

The UK government could legislate to require British companies not to use commodities in their supply chains that drive further deforestation in vital tropical forests. This would be far more effective than relying on action by tropical forest countries, many of whom have weak domestic environmental legislation which has demonstrably not been effective in stopping deforestation.

The omnibus bill in Indonesia – the global powerhouse of palm oil production – diluted the current environmental law within the country regarding permitting requirements and environmental impact assessments. In Cote d'Ivoire, the forestry code encouraged further unsustainable cocoa production and legalised large-scale deforestation in already ravaged areas. In Ghana, it is widely recognised that illegal logging for timber continues due to a shortage of forest wardens.

Putting the onus on tropical forest countries to reduce deforestation also creates a risk of potentially pushing trade into countries and regions with lower standards or poorer protection, as more developed countries stop deforestation. The resulting race to the bottom would mean that deforestation would not be reduced but simply moved to a country where it is easier to comply with the local laws.

But we can stop this from happened if we just stop purchasing the forest risk commodities in the first place. If Western economies really want to make an impact on deforestation in the global South, then they should move to stipulate that all their imported commodities should be sustainable. Only by destroying the major markets for the products of deforestation can we halt it.