To solve our healthcare staffing crisis, UK immigration policy must be re-examined

Shortages of over 50,000 nurses and midwives and 12,000 doctors pose a serious risk to patient safety according to a recent Health and Social Care Committee report, news which necessitates a rethink of our immigration policy, writes Kalan Irvine.

Many British citizens are unable and unwilling to work for the NHS due to low wages, poor working conditions like 12 and a half hour shifts and the NHS bursaries being scrapped in 2016 due to the Government stating that they felt it placed an artificial cap on the number of students that could study.

The Health and Social Care Committee's report found that high numbers of nurses, midwives and social carers are quitting their jobs and not being replaced, in order to improve work life balance, physical working conditions or a promotion which is all achieved by joining the private sector. A survey in October 2021 on NHS nurses found that out of all of them who were considering leaving, the most common reasons were due to feeling undervalued, under too much pressure, or exhausted and could find relief from this by joining the private sector or even taking a permanent career break from the medical profession.

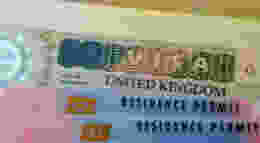

Bearing in mind that nearly half of the new nurses and midwives registered in the UK in the past year have come from abroad, it is clear that foreign workers are essential to filling current vacancies. The government must reassess our migration policy, as its current stance precludes a properly functioning health service. Any new visa regime must change to address this.

'Practical' thinking

Issues with current migration policies are not limited to the NHS and healthcare, and have been widely discussed across the public and private sector.

Ryanair boss Michael O'Leary, is seeking a more "practical, common sense" approach to post-Brexit migrant policy from the government, to allow more vacancies to be filled by people outside of the UK.

Crucially, Mr O'Leary believes that increased immigration will lead to a reduction in our current surging inflation problem, as it will result in increased competitiveness. The current price level sits at 9.4 per cent rather than the Bank of England target of 2 per cent.

Speaking to BBC Radio 4, O'Leary said, "people want good service, they want low prices. And we need a competitive economy for that. It is simply not acceptable to turn around to the vast majority of the British people and say, with nobody to pick or to harvest the food, 'please pay 20 per cent higher food prices.'"

In a survey of more than 2,000 staff undertaken earlier this year, nearly four out of five staff who were considering leaving (79 per cent) said that an inflation-busting pay rise would persuade them to stay. So any move akin to that suggested by O'Leary could go a long way towards helping to reduce the 62,000 medical professional shortage.

The government has said that NHS England is creating long term plans to tackle this shortage. There are plans to recruit 50,000 more nurses and midwives by 2024 through a £95m cash injection into recruitment to maternity services and £500m for social care, with NHS bursaries coming back.

This however is an unsustainable approach to tackle this problem. By throwing cash at the problem, national debt will increase substantially, which already currently stands at 96.1 per cent of total GDP according to the ONS .

Pay rise

Rising inflation has led to the government announcing that NHS staff will receive a pay rise of at least £1,400 with lowest earners receiving up to 9.3 per cent increased wages, but NHS workers say this does not meet the increased cost of living.

Outside of the NHS, government analysis estimated that more than 17,000 care workers were paid below the legal minimum wage of £9.50 an hour. No wonder there's a skills shortage to this seemingly unapproachable job, where the people who care for and save lives have no disposable income after spending it all to simply stay afloat.

What changes are needed?

New immigration rules came into place in the UK in February 2022. Care workers are now a shortage occupation, meaning that they can immigrate into the UK provided the job meets the minimum salary level of £20,480 per year. However, as of 2020/21, 93 per cent of care workers were paid below this rate. This points system is therefore discriminatory and should be abolished entirely or at least amended enough to a point where most workers can actually enter the UK.

By introducing a new 'practical' approach to how we handle migration policy, we will be able to radically improve the current healthcare and skills crisis and meet the NHS target of recruiting 50,000 more nurses and midwives by 2024. Focusing solely on boosting domestic hires into the sector to meet this goal is wishful thinking. The government has shown a lack of understanding of the needs of the sector by making it so difficult for foreign healthcare workers to come to the UK. Without the necessary change, our once thriving healthcare system will continue to struggle to meet the expectations of an ever-demanding public.