The Tory Brexit trap

Evgeny Pudovkin asks whether the Tories are capable of delivering a hard Brexit, whilst also fending off the looming prospect of a Corbyn government?

It may seem strange, but only last April pundits hailed Theresa May as a political genius. There was a touch of astuteness to her decision to call a snap election; hardly anyone saw an omen of impending disaster. Consumed by internal squabbles and navel-gazing, Jeremy Corbyn's Labour Party hardly seemed like a rival credible rival.

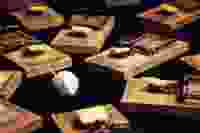

To be fair to May, her reasoning on an early election seems fair even in hindsight. If there was a convenient opening to boost her majority, it was last spring. It is the Prime Minister's other calculation – to use 'hard' Brexit as an opportunity to reach out to working-class voters – that deserves greater scrutiny. The consequences of this judgement still weigh on the party's medium-term electoral strategy.

May in Disraeli land

By taking on both the mantle of a 'hard' Brexit and social conservatism the Tories intended to appeal to the 'left behind' parts of our society – those, whose sympathies had hitherto lied with either Labour Party or UKIP. As a result, the Conservative's new electoral alliance would still include the well-off (who had no credible electoral alternative), but also the working class (keen on a 'hard' Brexit). Gains among the latter would offset the decline in support from the liberal middle-class Remainers sympathetic to David Cameron's 'modernising' brand of Toryism. In the true Disraelian style, May stole moderate Labour's clothes as they went bathing.

The Cameroons still retained the 'Cool Britannia' imprint. There were photo-ops with huskies, bicycle trips to Westminster and pandering to the green agenda. Last April, Theresa May showed up at factories, championing workers' rights and scolding the Thatcherite economic legacy.

It was, the Prime Minister concluded, not Cameron's 'buccaneering' version of capitalism – or Jeremy Corbyn's Trotskyite designs – that the country craved, but stability. Victory in the election would be the Conservatives' master-class in statecraft. Evidence that the mainstream centre-right can ride the wave of populism rather than being swept up by it.

We know how the story ends. Having lost urban middle-class constituencies like Richmond, the party failed to make sufficient gains in the North of England. The surge of turnout among the Labour-supporting youth further complicated matters. So, where do the Tories go from here?

Job half done?

One could still argue that the Conservatives' hunch to reach out to the working classes was justified. In the end, May has improved her party's standing with the C2 and DE socio-economic categories – from 26 per cent in 2015 to 38 per cent at the last election (according to Ipsos MORI data). The party now controls Copeland, Mansfield and Stoke-on-Trent South.

Northern voters' aversion towards the Conservatives could owe more to tribal inertia than to any substantive difference of opinion. If this is true, the Tories will stand a greater chance of winning them over next time around. Provided, of course, that the party sticks to a 'hard' Brexit as well as to its tough rhetoric on migration and security.

But here is the rub: what if the umbilical cord of tribal loyalties will prove stronger than thought? Another problem exists in Tory support being concentrated predominantly among the elderly. This makes the Brexit electoral coalition less sustainable.

Back to basics

This brings us to the second option the Conservatives should explore: shifting focus back to the economic issues. Competence on financial matters was the quality that David Cameron and his Chancellor George Osborne put at the heart of their successful campaign in 2015. Can driving home the message of economic prudency help the party get their electoral mojo back?

As long as 'hard' Brexit remains the Tories' policy, the answer is no. Inflation has picked up, largely due to the Brexit-induced weakening of the pound. Consumers will soon start to feel the pinch from lower real wages. Problems households face is underscored by the plummeting saving rate. Uncertainty around the format of the UK-EU future relationships may hinder business investment and disrupt trade links. In absence of post-2019 EEA transitional arrangements, adverse short-term effects on national economy from a 'hard' Brexit are likely to be negative.

To hard Brexiteers, this view may seem unnecessarily bleak. Perhaps they are right. So, let us be more open-minded. Assuming the UK gets a free-trade agreement on goods and loses much of the access to the financial passporting. Imagine also that such a deal goes through parliament. Potentially, this could offer upsides for exporters, especially in manufacturing. The non-urban electorate may feel the greater stability that lower migration brings. Yet these benefits will take years to bear fruit; the economic pain associated with post-Brexit adjustments will be immediate. As incumbents, the Tories will have to bear most of the burden.

Moderate Tory MPs see the way out in opting for the 'soft' Brexit with the UK remaining part of the European Economic Area (EEA). This approach has several benefits. For one, this can almost nullify the economic damage incurred by Britain's departure. It will also go some way to woe back some of liberal middle-class voters back to the party. On the downside, this will create the impression – and rightly so – of the party backsliding on their earlier promises.

There is no doubt that a way to relieve the Conservative Party from the political burden of Brexit. It would require establishing a cross-party commission to work out the right deal to pursue in negotiations. This plan has one major problem, however: it's just not going to happen.

Labour has no incentive to cooperate. Corbyn's electoral stock is bullish. Both he and his retinue want the next election to be fought as soon as possible. What sense does it make to help their rival get a smooth sailing on Brexit?

A way out?

Does it mean that the game is up for the Conservatives at the next election? Not quite. There is still a chance of climbing out of the hole. At the very least, the Tories seems to have started working towards that goal.

With regard to domestic strategy, the party has done away with May's 'Brexit alliance' and reverted to the liberal type. Chancellor Philip Hammond is beating the austerity drum with a renewed vigour. Downing Street is once again open for consultations with business leaders.

On Brexit, the government understands the need to disperse the damage associated with adapting to its new role beyond the EU. This would require achieving transitional arrangements it can fall on between March 2019 and the next election. Such a solution has Philip Hammond as its chief advocate, but is yet to obtain an unequivocal backing in Cabinet. The chances are, he will get it.

In September May is set to deliver her Brexit speech. Will she uphold the red lines she mentioned at Lancaster House?

The decision the Prime Minister face is a tough one. On the one hand, there is no clear majority for 'soft' Brexit. The latest YouGov poll for The Times indicates 58 per cent of Britons now want the government to prioritise economic benefits over migration in its talks with Brussels. Meanwhile, the Leavers stand by their choice.

But will the transition period ensure there is a soft landing to the 'hard' Brexit? One would hope so. Otherwise, there is a real possibility of a Corbyn government. The Prime Minister may feel a temptation to relax her negotiating stance and "own" the decision to shield the party brand from contamination.

May is an (in)famous shape-shifter. From a tentative Remainer she morphed into an ardent, authentic Brexiteer. An ostensible pioneer for the Cameroons, who dubbed the Conservatives a "nasty party", May had no trouble of catching the cadence of anti-globalisation tunes. One wonders what elaborate disguise will she put on next…