The perils of a post-Brexit diplomatic vacuum

Such are the divisions between Labour and the Conservatives that we risk being left paralysed in a post-Brexit diplomatic vacuum unable to build forge stronger with the US, while inhibited from rebuilding links with the EU, Andrew O'Brien argues.

Summer is always a useful period for reflection and it follows a particularly busy period in political life with the Chequers Meeting, the Brexit White Paper and recent the Trump visit.

I have lumped these events together specifically because Brexit and Trump are two sides of the same coin. The fractured political environment that Britain finds itself in is creating a paralysis which leaves us isolated and alone. It is fine for the United States to pursue an "American First" strategy. With its continent-sized economy and population as well as military preponderance – isolationism is a luxury which the United States can afford to pursue.

Britain, by contrast, is an island nation for which isolation is dangerous. Britain's diplomatic isolation in the 18th Century saw the loss of The Thirteen Colonies. This rupture almost destroyed Britain as a great power. In the 19th Century, Britain faced a more existential threat with the prospect of invasion from Napoleon with only the Royal Navy creating a barrier between it and the General's armies. And famously, in 1940 Britain stood alone against Nazi Germany, again the Royal Navy and the RAF doing just enough to prevent Hitler overrunning his final opponent.

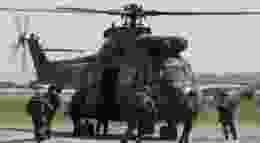

The last two cases saw Britain eventually emerge victorious, but only because of the folly of both Napoleon and Hitler deciding to invade Russia. We survived by the skin of our teeth, but we won through coalitions on the Continent and with the United States and Soviet Union respectively. Who would trust the Navy or Air Force to do the same given its current dilapidated condition?

Of course, this all might sound like ancient history and hardly the sort of comparison worth making in the modern context. After all, there hardly seems any prospect of war on the horizon, so perhaps we can afford to sit things out? Yet as we enjoy a barmy British summer, we should not ignore the ghost of 1914, where global catastrophe appeared like a bolt from the blue.

It is just as well there isn't a major threat on the horizon because Britain finds herself more isolated than at any point since 1940. Our previous Foreign Secretary can bluster about 28 nations joining the UK in expelling Russian diplomats following the Salisbury poisonings. However, this is the exception rather than the rule. It was also motivated more by fear of Russia than solidarity with Britain.

The simple truth is that the right is incapable of allowing the UK to form strong alliances in Europe and the left won't allow us to form strong alliances with the United States. We are effectively without a foreign policy because there is no national consensus on our future relations.

The right views Europe with suspicion. We are leaving the European Union of course and this will do great damage to our relationship with European nations. Anyone who believes that we can leave the European Union but remain close friends with the remaining members are deluded. Whether we like it or not, Europeans will view our departure as just another example of "La perfide Albion". Who wants to create binding security and diplomatic relationships with a flaky partner?

The obvious pivot would be towards the United States. Yet the left is no longer home to any Atlantist movement. Attlee and Bevin would not be welcome in the modern Labour Party. The election of Donald Trump has further hardened attitudes on the left. Perhaps the election of a liberal president in the mould of a Barack Obama might enable the UK to strengthen its partnership with the US, but even then it is hard to see the UK/US alliance being as strong as Thatcher/Reagan or Blair/Bush. One word "Iraq" is all that is required to stir up the left into paroxysms of rage.

In terms of Brexit we often talk about there being no majority of any particular form of deal. In terms of foreign policy, is there a majority for any alliances?

A future government will no doubt seek to avoid this by developing alliances with lots of smaller powers. Canada and Australia are obvious targets, with little domestic opposition likely. Japan and India will also be followed up. Though in the case of the latter, there appears little appetite for closer links. But let's not forget the case of France in the 1930s, however, where its "Little Entente" was totally inadequate to the scale of the threat that emerged from Germany.

The elephant in the room is China. Economically the UK under the Coalition and Cameron Ministries appeared keen on courting the Dragon. Yet there remains legitimate suspicion about its expansionist tendencies. Teresa May has also started to create tougher rules on company takeovers to protect "national security." The right is unlikely to be in favour of too close a relationship with China. The left is also unlikely to want a friendship with China given its human rights record.

The sad prospect awaits us of Britain pulling up the drawbridge not as a strategic choice but because we simply cannot agree on who our friends should be. This should worry us as much as Brexit, if not more so.

Tony Blair famously said that he wanted Britain to be a bridge between the United States and Europe, sadly we are currently now a Bridge to Nowhere.