Stronger regulation needed for agricultural pesticides

Two drugs companies on different continents developing drugs for different purposes, who unexpectedly find a huge conflict of interest in both profits, and global health and the security of food supplies. You could – in these Covid days – just about imagine a movie about it, a disaster film with slow-mo shots of scientists using pipettes with ominously coloured liquids, and patients sickening and dying as harried medics rush from bed to bed, while giant agricultural sprayers blanket fields with layers of poison just outside the window.

The story of Olorofim and Ipflufenoquin is not quite that dramatic – but the consequences could well be. It is a powerful tale of how our relationship – sometimes cooperative, sometimes competitive - with some of the oldest forms of life on Earth, microscopic and apparently quite simple, is a true matter of life and death, of battles which we are far from guaranteed to win. More, this is a demonstration of our inability to coordinate the actions of private pharma and chemical interests and the public good.

Chances are that you have been exposed to the tiny mould spores that cause Aspergillosis – a damaging lung infection - through your garden compost, plants, dust or your office air conditioning system. For most, this does not cause an issue, but the consequences can be severe for vulnerable individuals; those with lung conditions, a weakened immune system or requiring artificial ventilation due to severe flu or COVID-19. The condition kills thousands in the UK every year, with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis likely affecting up to 15 per cent of cystic fibrosis patients and 4.8 million asthmatics globally.

Our frontline medicines to treat Aspergillosis, and the only ones that come in tablet form, are azole-class antifungals. But resistance to this class of antifungals among our communities and hospital wards is increasing: the azoles often just do not work any more. Recent University of Manchester, NHS and Netherlands research found that 20 per cent of UK and Netherlands patients with Aspergillosis display drug resistance. Deeply concerning, given that 88 per cent of drug-resistant Aspergillosis cases result in death.

As an agricultural science graduate, I know about azoles in a different context – being sprayed, often in complex mixtures of pesticides, on our fields in industrial quantities, some 40 per cent of the total pesticides used. These accumulate in water and soil, and contribute to the development in resistance. The issue of resistance to azoles – and deaths – is particularly bad in the Netherlands, where they are used in enormous quantities to protect tulips. Yes, people are dying as a result of the pursuit of perfect flowers.

Yet there is good news. Enter, in the movie, a dramatic discovery, ideally by a handsome young scientist who has had to fight the establishment to win backing for her work. In real life, it is called Olorofim – and I don’t know what the scientists who developed it look like. In real life, that doesn’t matter.

In the movie, it might be rushed down the hospital corridor to save the life of a desperately ill young child. In real life it is saving lives daily. Demand for this new drug has been unprecedented, with the company developing it, F2G, having to temporarily close its doors to new patients.

Yet at the same time, there has been developed in the US a pesticide for agricultural use, Ipflufenoquin. It operates biologically in the same way, through the same mechanisms within the fungi, as Olofrofim. That means spraying it broadly on fields could rapidly induce resistance to the human drug. Its use could quickly make Olofrofim ineffective.

The University of Manchester has conducted urgent research into this disastrous cross-resistant relationship that could undermine the decades of effort that went into developing Olofrofim. The results led Professor Michael Bromley to say that “as a priority, approval of Ipflufenoquin for use in agriculture and other commercial sectors should be paused”.

Will our government listen to what our country’s leading researchers are trying to tell us? That we need to delay Ipflufenoquin approval in the UK and ring-fence the drug pathways associated with medicines like Olorofim to try and protect their efficacy? This is where our movie might move to the corridors of Whitehall, the gilded chambers of Westminster, as last week I brought a debate on this subject to the House of Lords.

Fungal diseases cause more than 1.5 million deaths every year, not far from that of tuberculosis and three times that of malaria. Yet, unlike those conditions that have plastered our media headlines for years, fungal diseases are still woefully neglected in our policy landscape.

As threatening as fungal diseases are to us directly, they also present a wider danger. A hefty 80 per cent of all plant diseases are caused by fungi. With 80 per cent of our food dependent on plants, it goes without saying that protecting plant life is essential for protecting our food security. The great Irish potato famine in the 1840s, the Bengal brown spot rice outbreak of the 1940s, the African wheat blight and the way our world’s coffee industry dwells in South America and not where it originated in South Asia reflect past occasions where fungi have defeated humans.

For now our – more or less – working agricultural pesticides are holding the agricultural line. But at what direct cost to human and environmental health? I questioned whether the Government had made a careful enough assessment of the long-term consequences of widespread fungicide use on our food supply, as in the case of Olorofim and Ipflufenoquin, but also far beyond.

Sixty-two percent of the world fungicide market consists of just six drug mechanisms of action, of which five are classed by the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee as having a high or medium-high risk of resistance. This suggests that a large proportion of the fungicides we rely on for our food are a time bomb of resistance that could provide future Potato Famine-like risks.

Yet the UK Food Security Report (2021) mentions fungal pathogens just three times in 322 pages. There clearly needs to be far more of a focus on them. I proposed an inquiry in the Special Inquiry Committee Proposals for 2024, which was unfortunately not selected as one of the Lords’ priority areas for next year. Last week I did not really hear how the Government sees fungicide use fitting into the growing pressures of fungal disease in both medicine and agriculture in a warming world.

Striking the balance between prioritising our food security with safeguarding our clinical treatments is a challenge that our Government – and the “Quadripartite”, a structure bringing together the World Health Organisation, the Food and Agriculture Organisation , the UN Environment Programme and WOAH (the animal health body), which has the global oversight responsibility - can no longer ignore.

It is clear – as the Green Party has long been saying – that on the farming side agro-ecological approaches – as the Exeter researcher Jamie Lorrimer puts it, “using life to manage life” – are essential, as part of a broader One Health approach that acknowledges human, animal, plant and environmental systems survival are all inter-related and interdependent. And we have to safeguard the human medicines, urgently.

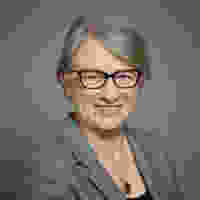

Prepared with British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy intern Lorna Flintham.

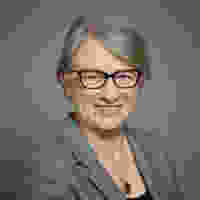

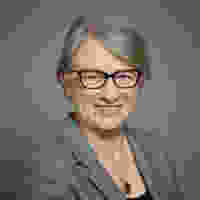

Baroness Natalie Bennett is a member of the House of Lords and led the Green Party from 2012-2016.