Moshe Kantor: Threat of nuclear terrorism is real

Thirty years on from Reykjavík, dialogue and cooperation between key states remain the best remedy to countering the nuclear threats we face, says Moshe Kantor.

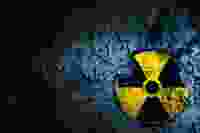

We live in uncertain and troubling times. We are rightly on red alert against the threat of what has now become conventional terrorist acts of indiscriminate suicide bombings, gun and knife attacks. But we are seemingly blind to the much more catastrophic and all too real threat of nuclear weapons falling into the hands of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (Isil) and other terrorist groups.

It is hard for us to imagine, but terror groups are alarmingly close to acquiring nuclear weapons. Security experts believe the Jihadi brothers Khalid and Ibrahim el-Bakraoui were plotting to make a radioactive bomb by kidnapping Belgium's nuclear programme chief in order to force him to let them into one of Belgium's two atomic facilities to steal nuclear material.

Nuclear proliferation, either by terrorist groups such as Isil or state actors like North Korea, mean we are living in a world confronted with a threat level the likes of which we have not seen since the Cold War.

It is worth noting then that this year marks the thirtieth anniversary of the 1986 Reykjavík Summit on nuclear arms reduction. Although the talks between President Ronald Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev collapsed at the last minute, the progress achieved during the negotiations proved seminal in curbing the arms race between the two sides, and paving the way for the signing of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty the following year. That agreement saw both sides agree to eliminate their respective stockpiles of intermediate and shorter-range nuclear missiles.

Since Reykjavik, further progress on nuclear-arms reduction and non-proliferation has been made. In 2010 President Obama signed a strategic-arms-control-treaty (New Start) with Russia, which, together with the establishment of a new inspection and verification regime, will see the number of strategic nuclear missile launchers reduced by half. More significantly, last July saw a deal reached to constrain Iran's nascent nuclear programme. The accord will keep Iran from producing enough material for a nuclear weapon for at least ten years and impose new provisions for inspections of Iranian facilities, including military sites.

Despite these achievements, it is frustrating greater progress on nuclear arms reduction has not been achieved. As the attacks on Brussels demonstrate, the threat of nuclear proliferation remains very real. North Korea, long a belligerent regional player, already has the capacity to launch a nuclear attack on Seoul and Tokyo. Experts predict that within the next decade they will have the ability to strike at the heart of the US. Meanwhile, tensions between Pakistan and India, both nuclear armed states, remain high.

As former US Defence Secretary Robert McNamara explained, unlike the application of traditional forms of military power, there can be no learning period with nuclear weapons. One mistake can destroy nations.

Furthermore, fissile material stored in ailing research facilities in the former Soviet Union, combined with an ever-growing contingent of disaffected young men and women hell-bent on perpetrating mass murder in the name of misguided ideological beliefs, mean the threat of a so-called "dirty bomb" attack in the heart of Europe is greater than ever.

It is for precisely these reasons that the International Luxembourg Forum On Preventing Nuclear Catastrophe, of which I am president, convened last month. Established in 2007, the Luxembourg Forum aims to promote international peace and security by developing practical policy solutions aimed at limiting nuclear arms and countering the threat of nuclear terrorism. The two-day conference involved a host of participating experts developing a credible blueprint of recommendations to be presented to and hopefully implemented by the world's major nuclear powers – US, Russia, China, UK and France.

Irrespective of the outcome of November's US Presidential election, it is vital that the victor takes heed of these recommendations and picks up the mantle of tackling the threats posed by nuclear armed rogue states and extremist groups. The current stalemate in discussions between the super powers cannot be allowed to continue.

As former President Gorbachev explained in his address to the Luxembourg Forum earlier this year:

"[Thirty years on from Reykjavík] we cannot be satisfied with the current situation. The window to a nuclear-free world, first opened in Reykjavik, is being shut and locked before our eyes. New types of nuclear weapons are being created. Missile defence systems are being deployed. The nuclear powers' military doctrines have been changed for the worse."

He is right – the threat of nuclear terrorism and proliferation is greater than ever. But as we have seen from Reykjavík and subsequent summits, dialogue and cooperation between key states, together with effective leadership, remain the best remedy to countering the nuclear threats we face.

This article first appeared on The Telegraph website on 8 June, 2016 and was syndicated with the kind permission of Moshe Kantor.