Look beyond ideology to understand terrorism

To avoid future cases like Shamima Begum we must avoid the general temptation to try to understand terrorism only in terms of ideology: the idea that there is a ripple of extremism percolating in society that has infected a few vulnerable people. Instead, we must look deeper to its root causes.

Shamima Begum has demonstrated another dimension to the threats from 21st century terrorism: how radical causes suck in ordinary people, making tragedies of ordinary lives. It's one thing to make a robust and unflinching response to an 'enemy' organisation, another to a young woman with a new baby.

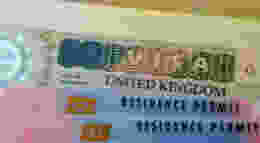

The UK needs to avoid a future where there is the potential for anyone to be radicalised – where there is a constant cycle of Shamima Begums, the complex tangles of personal stories with moral questions over citizenship rights and responsibilities. Even now Donald Trump has argued all British citizens caught up with ISIS should be brought back and dealt with by the UK.

Policymakers here and internationally need to get to the root causes of how radicalisation occurs. There is a general temptation to try to understand terrorism only in terms of ideology: the idea that there is a ripple of extremism percolating in society that has infected a few vulnerable people. This is certainly the narrative that governments in the West have tended to focus on over the years since 9/11, but it doesn't tell the whole story. Evidence suggests there are several other key drivers and some of these are going to become even more important in the coming years.

Four major global trends stand out as giving cause for concern. The first is an anticipated significant increase in the world's population over the next century, from around 7 billion currently to more than 9 billion by 2050. This will be accompanied by a surge in the number of 15 to 30-year-olds in many parts of the world. Following a long-term trend, increased numbers will shun rural communities and instead choose to live in urban areas like towns and cities.

Experience suggests that societies with high numbers of young people – what demographics refers to as "youth bulges" – and increased pressure on urban infrastructure can become destabilised and volatile, leading to a very increased risk of extremism and violence. We have seen it in Asia, the Middle East and Central Africa, with the rise of groups like Boko Haram, Al Shabaab, Al Qaeda and Islamic State. Predictions of massive population increase in coming decades for many parts of Africa and Asia in particular, represent major causes for concern.

Climate change and migration will be two major factors going forward. We are already seeing the impact climate change has had in Africa, the Middle East and Asia, where it has contributed to the emergence of terrorist groups like Boko Haram and Islamic State. Between 2005 and 2010, Syria experienced the worst drought in its recorded history. It destroyed agriculture in the eastern half of the country, leading to the collapse of rural communities and a mass migration of the rural population, who abandoned their countryside homes and moved to urban areas in search of new livelihoods. At the same time, Syria experienced an influx of refugees from Iraq as a result of ongoing conflict. The urban infrastructure of the country couldn't cope with the surge in population and collapsed. Within a year, there was a popular uprising against the Assad government that is often viewed solely in terms of the Arab Spring in that region and the subsequent rise of Islamic State.

Environmental factors like climate change are ruining people's livelihoods, destroying bright futures, and making people desperate. That unrest, violence and ultimately terrorism become much more likely should not surprise us. And yet, the focus for counterterrorism is too often just on ideology. It is difficult to design counterterrorism policy around major global trends as they require a much more holistic approach to tackle them effectively. They are also longer-term threats, and there can be reluctance to think beyond what is immediately around the corner. For example, the US military has already explicitly identified climate change as a strategic threat, but the US government is not yet giving it the same level of attention.

Over the coming years, the harsh reality is that we can expect to see climate change playing an increased role in setting civil wars and terrorist conflicts in motion. This, combined with population growth, will also feed into massive migration, and one challenge will be how to integrate migrant communities within host countries to avoid a rise in ethnic tensions and extremism.

Another contributing factor is likely to be the decline of the USA as the dominant global superpower. While the US may yet end the 21st century still technically the world's most powerful state, its economic power relative to major rivals has been in decline for some time and this inevitably will gradually result in a loss of military superiority. As the margin between it and other powers fades in the coming decades, there will be a levelling of the playing field, allowing a number of states to exert tremendous control and influence within their regional hubs. Initially, these rivals will gain parity only in narrow specific niches, but their dominance will spread as the century progresses.

The fourth critical long-term trend is the struggle for control of natural resources. As economies outside the West continue to grow, they become increasingly resource-hungry. At the same time, demand in the West shows no signs of lessening. As competition to sustain supplies intensifies, the potential for conflict will increase. Clashes are likely to focus on establishing and protecting friendly regimes in supplier nations, rather than manifest themselves through open, direct confrontations between major players. The result, though, is that those supplier nations – particularly in Africa, the Middle East and Latin America – will be increasingly vulnerable to destabilisation and internal conflict.

At the moment, we are seeing a gradual awakening to some of the problems that lie ahead, which is encouraging, but it isn't across the board. Of course ideology is a factor in terrorism, but focusing on this alone as the major cause of terrorism is both misleading and incredibly dangerous. Government leaders, policy-makers and counterterrorism experts need to stop shying away from engaging with the role of big topics like climate change, control of natural resources and global migration and work together to understand how they impact on the threat of terrorism and what will really work when we think about counterterrorism in those contexts.

Looking ahead, the question is not simply what form terrorism will take in the future, but rather what major global processes will drive it. What international forces and events will ignite and stir terrorist conflicts in their wake? If we can start to anticipate these now, we will be in a much better position to combat threats we know are coming.