Freedom to flourish depends on regulatory autonomy

For the return of our national sovereignty, and for the country's prosperity in the decades to come, without regulatory autonomy, withdrawal from the EU will be incomplete, say Shanker Singham, Dr Radomir Tylecote, and Victoria Hewson.

Withdrawal from the EU must mean regulatory autonomy for the United Kingdom – sovereignty over its regulations. This reflects the democratic mandate of the 2016 referendum and the 2017 manifesto commitments of the Conservative and Labour Parties, and will propel growth and competition in the economy. It is also necessary for the UK to be able to sign advanced trade agreements with countries around the world.

The United Kingdom has a unique opportunity to use withdrawal from the EU to grow its economy and become considerably more productive. It is vital that nothing is done to take these benefits off the table. But for procompetitive regulation, regulatory autonomy is vital.

In her Lancaster House speech in 2017, the Prime Minister outlined that Brexit would mean legal independence through an end to European Court of Justice jurisdiction in the UK, and that the UK must be free to execute an independent trade policy, striking agreements with countries outside the EU, outside the Customs Union's Common External Tariff. In her speech at the Mansion House in March 2018, she stated that this meant our regulations would "achieve the same outcomes" as EU law, but need not be identical.

To deliver an independent trade policy and substantially more prosperous economy, the UK must have the ability to change its regulatory system from the EU's acquis when it seeks to do so, and when beneficial for trade agreements. A 30% reduction in regulatory distortions between key trading partners by 2034 could mean GDP up to 7.25% higher than it would otherwise have been.

The UK must be able to deliver the following five points:

– Autonomy for the UK to make its own regulation (for both goods and services)

– Autonomy for the UK to set its own standards (for both goods and services), which can include using global standards.

– Autonomy for a UK system of conformity assessment (able to assess conformity to UK and EU standards and regulations)

– Unilateral recognition by the UK of EU regulations, standards, and its conformity assessment system (able to assess conformity to EU and UK standards and regulations)

– Seek recognition by the EU of the UK's regulations, standards, and its conformity assessment system

For actual withdrawal from the EU to be achieved through an end to EU jurisdiction, and for the benefits of pro-competitive regulation, domestic regulatory autonomy needs to be the starting point. But this does not mean divergence in all areas – being able to diverge does not mean one will.

Mandatory harmonisation of regulation through the alignment of regulations themselves (as opposed to alignment of their goals) would fail to deliver the benefits of leaving. UK lawmakers may choose to retain and follow EU regulations at certain times and in certain sectors, but they must have the ability to choose not to do so.

The regulatory system the UK needs has three components:

– The first is in regulations (rules made by an authority, especially for products and services)

– The second is standards (demonstrating a product or service meets those regulations, or marks of quality in performance or safety – and where the functioning of the EU's standard system means that continued alignment would imply continued EU legal sovereignty).

– The third is conformity assessment (the system of bodies, e.g. firms, laboratories, and professional bodies, which assess conformity to standards, and provide certification).

The UK should be putting forward an open and constructive offer to the EU. Recognition by the UK of EU regulation, standards, and conformity assessment is a necessary part of this open offer. This will mean institutional competition for the UK economy, commercial competition from EU imports, and avoidance of unnecessary trade barriers on imports.

In turn, while it is to be expected that recognition by the EU will vary by sector, for the EU not to grant recognition to UK regulations, standards or conformity assessment would constitute creating new trade barriers (because at the point of withdrawal there will be UK-EU alignment). Commitments made by both parties in the WTO, international fora, and existing advanced trade agreements present a framework to build on.

Because regulations will still be fully aligned or completely recognised at the point of Brexit, there is a unique opportunity for both parties to offer maximal recognition – achieving mutual recognition between the UK and EU.

This opportunity, where an FTA is being negotiated by parties with identical or fully recognised regulation, is unique. The UK should therefore seek maximum mutual recognition on day one, and equivalence mechanisms in the EU that allow this where they do not exist already. Any differences after this that result from the parties changing their laws and regulations should be managed by permitting the withdrawal of recognition where the change results in the parties' regulatory goals not being met.

Negotiating this with the EU will be challenging, but this is too important a principle to abandon. If the EU will not accept it, it will be further isolated in a world where regulatory recognition and good regulatory practice is increasingly the preferred pathway to lowering trade barriers. Pro-competitive regulation is essential for the UK economy, and the vital first step is regulatory autonomy. The idea that the UK Government would decide in advance to be tied to whatever future regulation the other party produces, without UK representation in its institutions, would be extremely unusual. It would threaten our competitiveness, and our democracy.

Pursuit by the UK and EU of as much recognition of each other's regulatory systems as possible allows each to diverge and to pursue its policy priorities. In the UK, this should mean the reform of regulations to encourage competition and consumer welfare.

EU regulation is becoming more damaging to consumer welfare and growth, placing the innovative SMEs that are the lifeblood of our future economy at a disadvantage to large incumbents. It is widely acknowledged that the EU is now exporting this prescriptive approach to third countries.

The direction of travel of EU regulation means that, once secured in negotiation, the gains from pro-competitive regulation will grow over time. It is precisely this direction of travel that creates the potential gains, and we provide examples across a range of sectors illustrating this.

There have been developments in the global trading system, through the WTO, bilateral and platform free trade agreements, and mutual recognition and regulatory cooperation agreements, which provide a legal framework for the kind of ambitious free trade agreement with advanced regulatory recognition that the UK is seeking and that this paper recommends.

The opportunity needs to be taken now, and the implications of the choices the UK takes are fundamental. For the return of sovereignty, and for the country's prosperity in the decades to come, without regulatory autonomy, withdrawal from the EU will be incomplete.

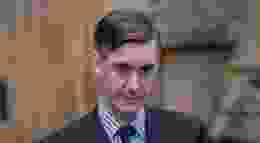

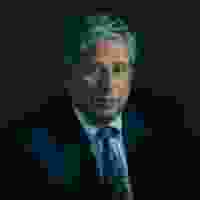

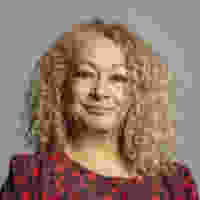

Shanker Singham is Director, Dr Radomir Tylecote is Senior Research Analyst, and Victoria Hewson is Senior Counsel of the International Trade and Competition Unit at the Institute of Economic Affairs – one of the world's leading specialists in trade and competition policy.