England beat Germany in the football, but in the field of Social Care, Germany cruises to victory

After a year which has seen England and the rest of the UK's social care systems come under major scrutiny for the ways they are funded and maintained, Kari Gerstheimer compares and contrasts England's system with that of Germany, and finds that the latter's comes out well on top.

Last Tuesday, England triumphed against Germany in the last 16 of the Euros, on the road to an occasion that could – pending 90 minutes – mark the beginning of the Great British Summer we all so deserve. History has seen 15 wins to Germany and now 14 to England. Our nations are close competitors on the football pitch, indeed great rivals. On another 'field', however, the Germans are still way out in front. This is the field of social care.

Let's read the report.

Our match-up begins in 1995, a few years after German reunification. At this point, Germany started to overhaul its social care system, realising that the existing one would not be able to cope with the pressures of an aging population. It implemented its Long Term Care Insurance model which was then upgraded significantly in 2008. England has faced similar demographic changes but has not done much to adapt. Several governments, starting with New Labour, have tried and failed to reform; numerous white papers, green papers and consultations have led to no constructive outcome. On these grounds, we must award an early goal simply for purpose and efficiency. 1-0 Germany.

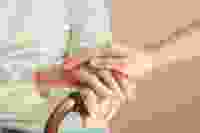

The picture worsens for the Three Lions when we get into policy. In England, not many people can access publicly funded care. It is accessible by a means test, and a tough one at that, with those having over £23,250 in savings required to cover the entirety of their care costs. Germany, on the other hand, has universal basic support. Everyone gets a certain amount of help from the state, not just the very poorest people in society. 2-0.

The German arrangement pools risk. Each citizen pays in a small amount, calculated as 2.5% of income, with employers paying half. It is not perfect – people on average salaries can still be hit with large bills if their needs go much further than what the state covers – but it is certainly better. Basic insurance significantly reduces the chances of people incurring catastrophic costs. Unfortunately, that is a third goal to Germany.

They are not finished yet. We concede again in the game's final minutes, on the issue of provider market stability. Many English care providers are going bankrupt or returning their under-priced contracts to local authorities, falling victim to central and local government funding cuts. Access Social Care research, conducted in partnership with academics from Oxford University, shows that it is England's poorest areas with the greatest needs that have had to make the biggest cuts to their adult social care budgets. Authorities in these areas are more dependent on central government funding for their care services rather than local revenue sources like business rates.

On the other hand, Germany's provider market functions well, underpinned by a nationally set and guaranteed funding level which is regularly renegotiated to account for things like rising costs. In recent years, there has been a spike in new care providers entering the market, confident that their fees will be met or for profit-seeking companies, that there is money to be made.

Having lost its Social Care Euros fixture a resounding 4-0, the turmoil of England's care system now reaches a new level. We must hope that this moment of national embarrassment will push the government into action.

When reform does finally come, we need more than just the Dilnot Cap, which will only address the issue of high personal costs. We also need a more generous means test, assuming the insurance option is still considered too pricey. We need to see an increase in funding for local authorities so they can pay for the care their constituents need so badly. And we need a new settlement for care workers to deal with the chronic labour shortage, bringing pay into line with the NHS to stop the outflow of care professionals to better-paying positions in, for example, supermarkets.

Time is of the essence. The World Cup is just around the corner.