COVID showed we can house the homeless; Storm Eunice showed we don’t want to

Adeem Younis writes that while we stepped up to the plate to help our homeless during the generational COVID pandemic, Storm Eunice showed that our day-to-day attitudes towards the homeless are yet to fundamentally change.

During the first lockdown, the government suddenly donned a humanitarian mask. Their unprecedented commitment to house all homeless people overnight was certainly a break from the past. However, the failure to offer the same level of support over Storm Eunice highlights the hollowness of our government's pandemic recovery rhetoric.

When the UK government announced the 'Everybody's In' campaign to house all of England's roughly 6,000 homeless people, it was lauded by campaigners as the biggest state intervention in history and a turning point for a Tory Party which had – against all odds – become the party of big government.

Yet their failure to do so in the wake of Storm Eunice's record-breaking winds shows reveals exactly what the government thinks of rough sleepers. In their eyes, they're dangerous vectors of disease, not vulnerable citizens who have fallen through the cracks of the state.

By April 2020, 90 per cent of rough sleepers had been housed and by September 2020 there were 11,000 rough sleepers in temporary accommodation and 19,000 in full-time accommodation.

This was a global trend. In Australia, the ruling right-wing Liberal Party housed 33,000 rough sleepers into temporary accommodation and hostels. However, this policy, as successful as it was, has since been dropped. The new normal, it seems, also means living with the policies of the pre-pandemic even if COVID ended up providing some valuable solutions.

Support for the homeless was not on the table during the most recent crisis in the UK – Storm Eunice – and the responsibility for the homelessness crisis has been handed back to struggling charities and non-profits, who are even more stretched after the pandemic.

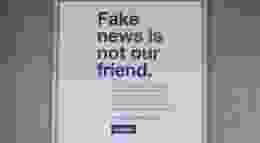

For this government, housing the homeless during COVID was less about trying to find a permanent solution to the crisis but a useful PR stunt and a way of managing a group of people too often seen as dirty vectors of the disease.

The reality is Storm Eunice was just as dangerous for homeless people as COVID was, if not more. With winds of up to 92 Mph, it was one of the strongest recorded in the UK's history. The storm claimed the life of a woman in her thirties, hit by a blown-over tree in London. Indeed, the government's official advice was to stay inside during the emergency, with motorways closed and many railway services cancelled – but how can you stay inside, if you have no inside to go to?

The Conservatives are traditionally the party of sound finances. Even if we can't appeal to their emotional hearts and we buy into their mantra of personal responsibility, surely they can be persuaded by the failed economics of homelessness?

Homelessness breeds desperation, hopelessness, and a lack of self-worth which in turn leads to petty crime, anti-social behaviour, and mental illness, costing vital resources of police and social services which could go elsewhere. Indeed, in the UK, research reveals that if 40,000 people were prevented from living on the streets for a year, it would save the government £370 million. The cost of homelessness in 2012 was reported to be £1 billion for the year.

COVID is noticeably a much bigger problem in the US than it is in the UK or Australia. Pre-pandemic there were around 600,000 people homeless in the US in a population of 300 million or 0.2 per cent. Wealthy and increasingly unaffordable cities are known for having a bigger problem with homelessness. Indeed just five states: D.C, California, New York, Hawaii and Oregon account for 45 per cent of homelessness.

Every year 13,000 homeless people die. With no nationwide lockdown in the US, there was no incentive to create a national plan of action – albeit even temporarily during the pandemic – so little has been done to reduce homelessness. The rise in unemployment and the lack of a government-backed furlough scheme exacerbated the problem and made it much more visible.

COVID is the first of many disasters that is likely to befall the US, as well as the rest of the world. As the world grapples with the climate emergency, forest fires and disasters like the Texas freeze will only become more frequent. The rise of A.I and computer automation may cause higher unemployment, whilst a cost of living crisis, tax rises, and inflation will make homelessness much more common – unless we act now.

It's also clear that charities and third parties are incapable of dealing with this issue on their own. According to a survey from the US-based National Alliance to End Homelessness, US homeless charities are engulfed by staffing shortages and lack of accommodation both short term and long term.

Boris Johnson wants to 'level up', and President Biden wants to build back better. One way to do that is to ensure homeless people are sheltered and that schemes are put in place to lift them out of poverty. At present, homelessness adds an extra burden to both the social security system and stretches the resources of the police.

With the winds of Storm Eunice having now abated, we are reminded once again that homelessness is not an inevitability, but rather a consequence of intentional government inaction. A problem that, as we've seen, can be solved overnight.