British defence requires more than kicking out Russian spies

With the world of espionage having evolved, Dr Rory Cormac argues our defences must evolve at the same pace, and must take into account more than simply seeking out enemy spies.

We are living in an era of covert competition. After two decades chasing terrorists, hostile states are firmly back on the West's agenda. Well over a hundred Russian spies operating under diplomatic cover have been kicked out of European capitals in the first half of this year. Meanwhile, British intelligence agencies have warned about Chinese espionage, especially in the fields of research and intellectual property.

The bigger problem is that spies do not just spy. Sometimes, states use intelligence agencies as a form of power: to compete, meddle, and influence. This takes secret statecraft beyond the more passive realm of watching and listening to something more active and impactful.

We focus too often on headline-grabbing coups, electoral interference, the supposed risk of a so-called "Cyber 9/11", and attempted assassinations. In reality, the vast majority of attempts to weaken governments and undermine democracy do not end in a big bang. Rather, they are nebulous, gradually chipping away at authority. In the words of one former MI6 officer active in the Cold War, 'one must not think in terms of spectacular coup, or dramatic feats of irregular warfare, but rather of a continuous sapping process.' And, crucially but often ignored, it is intertwined with our own domestic politics.

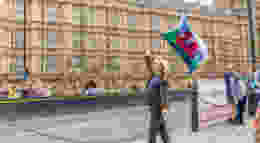

The goal is not necessarily regime change, but to disrupt, distract and divide: to destabilise and keep the target off balance. This might involve working through individuals with access to parliaments, international organisation or even universities. They might be individuals already operating of their own accord, thereby requiring, at most, some light coordination, or they might be directly controlled by the state. Alternatively, they might be unwitting idiots.

Critics accuse China of using covert political action to discreetly further Beijing's interests around the world. In November 2021, the head of MI6 warned about Beijing attempting to exercise undue influence over the Chinese diaspora and distort public discourse and political decision-making across the globe.

Just months later, MI5 warned that an alleged Chinese agent had infiltrated parliament and sought to interfere in British democracy. She had managed to build links with serving and aspiring politicians across the political spectrum, including through various donations. She is likely to be one of many of what President Xi calls 'magic weapons'.

Covert political action works hand in glove with propaganda and influence operations. Neither are new, and we should be wary of both over-hyping the threat and treating it with the neophile's bonanza of ill-defined buzzwords. It is important not to fetishize the revolutionary impact of social media. The aims are the same as ever: to exploit division, widen gaps in the population, and undermine trust in authority.

The internet era has, however, brought three core changes.

First, propaganda is now conducted at a higher tempo and volume than ever before. It is less skilful, conducted by armies of trolls and bots churning out volumes of trashy content. Russia may be the most infamous here, but dozens of states use information operations to spread unattributable material overseas.

Second, big data allows mass profiling and micro targeting. Propaganda – and even intimidation – can be neatly tailored to a much more individual level, playing on individual fears.

Third, the dramatic demassification – or fragmentation – of the media over the past twenty years makes controlling the narrative more difficult than ever. Propaganda therefore seeks to spread confusion and distrust; it is disruptive, chipping away at the adversary's version of the truth. Multiple contradictory Russian lines about anything from Ukraine to the poisoning of Sergei Skripal is testament to this.

Combined, Covert political and influence operations sow confusion, breed insecurity and uncertainty, undermine faith in institutions of authority. It is continuous and intangible.

Even in an age of declining secrecy, this covert competition will continue. We need to better understand it, engage in it, and defend against it.

Defence requires more than kicking out Russian spies, although that is an important start. We need to think carefully about exposure – and then to calibrate it accordingly. In some cases, giving too much publicity to hostile activity breathes oxygen into otherwise moribund operations, or it creates paranoia and distrust of its own. It risks cultivating the image of President Putin – admittedly diminished since February – as some sort of darkly omnipotent genius playing 4D chess with spies and saboteurs across Europe, rather than a huckster playing confidence tricks. Likewise, debunking disinformation is important but needs to be done in a coherent manner which cuts through among the target audience, without generating more cynicism and "both-sides-ism". Overplaying the hidden hand can be just as dangerous as neglecting it. A foreign agent registration act, as in the US or Australia, could also bring benefits in disrupting hostile activity.

Beyond this, it is vital to get our own house in order. The best defence is preventative: to sort out our own internal divisions. This would deny adversaries the ripe and exploitable grievances necessary for successful operations. Division and inequality create a breeding ground for foreign subversion, exacerbated by culture wars and toxic public discourse.

It should go without saying that governments of the day should not be spreading mistruths of their own. It all adds to a decline in trust, cynicism, and polarisation. We need to recognise the interplay between foreign and domestic.

Democracy does not necessarily die in darkness as the saying goes; neither will it end in a flash or a bang. Rather than a coup or violent insurrection, it will be the steady drumbeat of subversion and disruption carried out in broad daylight that has the most corrosive effect. We are a sitting target so long as our polarized communities and toxic populism create divisions that adversaries can readily exploit. We must not let them.