Action needed to address impact of palm oil

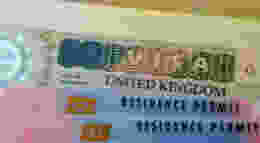

Open a packet of biscuits, pick up a bottle of shampoo, dig into a tub of ice cream, and odds are, if you squint hard at the tiny print of the ingredients list you’ll find "palm oil". In non-EU products it may well be simply “vegetable oil” or “vegetable fat”. And then there’s a long list of fancy, disguising names of palm oil products, from Palm olein to Elaeis Guineensis.

Around 90 per cent of that palm oil comes from a few islands of Indonesia and Malaysia; areas that were once lush tropical rainforest and are now monoculture plantations. That’s a monoculture of plants not even native to South East Asia – the palm, long grown in Africa in mixed, healthy forest plantations, was only brought across the globe 100 years ago, initially as an ornamental.

We know that around the world plantation agriculture is linked to human suffering and ecological destruction – rubber, tea, tobacco, sugarcane. And the destruction in Indonesia's forests today – as in other plantation systems - has its foundation in European colonial activities.

One stark historical example is the Dutch exploitation of the lucrative spice trade, particularly the cloves of the Maluku Islands, often referred to as the "Spice Islands." During the colonial period, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) held a monopoly on the spice trade, exercising strict control over the cultivation and distribution of cloves. The indigenous people of the Maluku Islands, who had cultivated cloves for generations, were thrust into a system of forced labour and were subject to harsh regulations and taxation by the Dutch authorities.

This legacy still lingers within Indonesia's corridors of power. It is founded on the ideology that some are entitled to exploit while others must submit. In the shadow of the forests, corruption thrives. Clientelism drives illegal deforestation, mining, and resource extraction. The private sector, wielding immense power, entwines itself with the politicians, resulting in a symbiotic relationship where political loyalty is rewarded with personal favours.

These issues are set out in a report by academics that was recently presented in London by the Forest Peoples Programme, which focused on the impact on indigenous communities. Their lands, sacred and ancestral, are often seized by private companies seeking resource extraction. This dispossession echoes the colonial disregard for indigenous rights, perpetuating a cycle of injustice.

The disregard for environmental and social assessments by private companies displays a serious lack of concern for environmental consequences. State-controlled media further compounds the problem by limiting coverage of environmental injustices, perpetuating the narrative of exploitation, and blocking the spotlight being shone on civil society activists engaged in the struggle to make change.

Civil society, the bedrock of democratic change, is in a precarious position in Indonesia. Its spaces are shrinking, while the skills and knowledge needed for effective advocacy are lacking. Yet, civil society is vital in advocating for sustainability, and represents community-driven action for local governance and land rights.

A visible military and police presence in forest areas is commonplace. Authorities are deployed to suppress political dissent and protect illegal resource extraction.

International Responsibility and Neocolonialism

This is not just horrible events far away – it is part of a system in which the UK is deeply enmeshed. The money that feeds into the corruption comes from global companies, part of a global supply chain that perpetuates environmental degradation and political dysfunction.

That means UK foreign policy – and aid policy (much diminished as that aid is under this government) – must focus on supporting local non-government organisations and civil society to develop their capacity. “Firefighting” these injustices, reacting to the worst and most egregious examples, is not enough. Real change demands providing the tools and knowledge needed for Indonesian civil society empowerment.

But more, it demands action to make multinational companies responsible for – ultimately unable to continue with – systems that underpin the environmental and societal destruction. That’s what I – and many others – were working to do with the recently passed Financial Services and Markets Act. The House of Lords inserted into it a clause that would have imposed a mandatory due diligence requirement on financial institutions to prevent the financing of illegal deforestation.

A modest measure, far less than the responsibility of due diligence that the European Union has imposed within its borders. Nonetheless, too much for the government, which led the House of Commons to delete the upper house’s work. Although there was a concession – a Treasury review to look at the issue.

Campaign groups are calling for far more: a proper due diligence law, so that multinational companies are forced to take responsibility for the damage their suppliers do, and an update to the Bribery Act of 2010 – now clearly inadequate and well out of date, with the UK a “major facilitator of corruption internationally”.

We cannot trust the financiers or the multinational companies to police themselves. They have to be policed. We in the Global North are comprehensively failing to do that. It is traditional, indigenous systems, as abused and attacked as they are, that are the chief bulwark against even more destruction on this battered planet.

Three hundred and seventy million indigenous people make up less than 5 per cent of the world’s population, yet they manage around 25 per cent of the land surface, which holds 80 per cent of the remaining biodiversity. Local communities have proven time and again to be the best custodians of the natural world – the natural systems on which our economies, our societies – our lives – are totally dependent.

Supporting them requires significant action in the forthcoming King’s Speech, including tackling bribery and corruption and reining in our criminal, fraud-ridden financial sector. Even the government, having passed its second Economic Crime Bill in two years, has acknowledged that more needs to be done.

This article was written in collaboration with Aziz Foundation senior intern Zoheb Ali

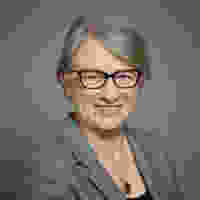

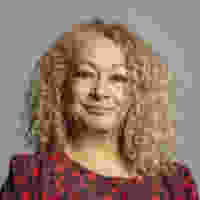

Baroness Natalie Bennett is a member of the House of Lords and led the Green Party from 2012-2016.