We haven't learnt our lessons from Covid

The world breathed a sigh of relief when Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the Director of the World Health Organisation (WHO), declared recently that the COVID-19 and Monkeypox global emergencies had ended. But the story isn’t over quite yet. The WHO may no longer categorise these diseases as emergencies, but the world’s lack of effective prevention measures means it won't be long before we face another global public health emergency.

This has all happened before. Sadly, the world was not ready for a pandemic in 2019, despite warnings from public health experts that the increase in regional outbreaks would eventually lead to a disease that could spread at an exponential rate. In a report commissioned by the WHO, the Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response (IPPPR) explained that “COVID-19 still took large parts of the world by surprise. It should not have.”

Indeed, the authors of the report were among those who had warned prior to 2019 that we needed better disease surveillance, adequate supplies of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and international cooperation to curb the spread of outbreaks.

We repeatedly ignored these recommendations even when faced with the quick succession of disease outbreaks in the first 20 years of this century. As the IPPPR stated, “despite the consistent messages that significant change was needed to ensure global protection against pandemic threats, the majority of recommendations were never implemented”.

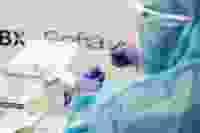

I was a first-year paramedic student in London in 2019, working on a frontline ambulance when those of us in healthcare still believed the few cases of novel coronavirus in the UK were isolated clusters and not the beginning of a global pandemic. We were wrong. Even though public health experts had warned us for decades that a world-changing pandemic was coming, we were unprepared.

Three years later, we still have not learned our lesson. According to the Global Health Security Index report in 2021, the world is dangerously unprepared for future epidemic and pandemic threats. Since 2000, there have been over 70 disease outbreaks around the globe, and the rate of these outbreaks has been accelerating.

So, how do we learn from our mistakes?

Even with the COVID-19 and Monkeypox global emergencies over, governments should keep public funds directed towards public health efforts. While it might seem like these funds should now be redistributed to other government sectors, to do so would be a repeat of the mistakes we made after the end of the SARS pandemic, when the urgency nations had felt during the crisis gave way to global apathy for public health preparedness and promises of policy reform going unfulfilled. We must use public health funding to prepare for more than just the known imminent threats; we must prepare for future threats as well.

How we fund public health both domestically and internationally has so far been shortsighted, failing to provide adequate reserves of equipment needed for future outbreaks. Our ability to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic was hindered due to a prolonged lack of adequate stocks of PPE, testing kits and vials for vaccinations, all of which are paramount to respond to outbreaks. This cannot be repeated.

Funding also must go to cataloguing new diseases. The easiest way to stop an outbreak from becoming a pandemic is to have effective local and regional disease surveillance in place to catch the outbreak before it spreads. While existing projects such as PREDICT create preemptive catalogues of viruses to allow for rapid detection and response, their work for the last 30 years still doesn't account for over 500,000 unknown viruses.

If we are to become preemptive rather than reactive, we have to identify unknown viruses as well as their hosts, ecology and drivers. Projects like the Global Virome Project aim to do that, but they will require consistent international support or they will fail. This happened in the wake of the Ebola outbreak, when donors including the US and World Bank gave $19 million USD to Liberia for disease surveillance just to have those funds run dry, leading to supply shortages and diseases going unrecorded.

If international organisations are going to fund projects, they must plan for longevity. This comes down to choosing the right outreach projects. The World Bank's new Pandemic Fund is focused on preparing low- and middle-income countries for future threats. Applications for their first round of funding, totalling $300 million, have closed this month. The projects they are looking to fund are high-impact – and high-cost. To avoid repeating past mistakes, the focus should also be on low-cost interventions which can be spread to the masses over an elongated time frame to achieve a prolonged impact. These could include programs like education and access to clean water for safe drinking water and handwashing.

We cannot wait until the next global public health emergency to establish these measures. The time is now, and it is in the global interest to prioritise prevention and targeted interventions at the source of outbreaks and disease spread. The public health programs funded by international organisations, including essential but expensive disease surveillance, must be continuously supported and not abandoned like they have been in the past.

Luc Woodall Gillard is an expedition medic and photojournalist and a political commentator with Young Voices UK.