The UK needs greater integrity in political campaigning

Following months of speculation, the general election campaign is underway and with it an unprecedented level of scrutiny of our politicians. Thanks to rolling news and social media, every policy, speech, campaign stunt, and mishap is magnified and picked apart in a way not witnessed before.

One way this can be seen is evident on the BBC’s Sunday with Laura Kuenssberg politics show. During the election, the show will fact-check politicians after each interview outlining the claims that are less than accurate. Politicians bending the truth as a matter of course is now so baked into our political discourse that it takes a sustained journalistic effort to challenge it.

This unhealthy trend is not helped by the explosion and democratisation of artificial intelligence tools that can easily and cheaply create deepfakes to try and discredit politicians. We witnessed that at the Labour Party Conference last year when a deepfake audio clip emerged of what sounded like Kier Starmer verbally abusing his staff. From Moldova to Northern Ireland, voters across the world have been fed false material, generated by AI that can ruin reputations.

This is why this year’s World Economic Forum’s Global Risks report identified misinformation and disinformation as the biggest short-term risk facing the world. If voters lose trust in their own politicians, it provides the perfect environment for others to influence the outcome of elections. For this reason, just as the 2015 UK general election was seen as ’the first social media election’, many have dubbed the current content ‘the first AI election’.

The challenge is that by focusing our attention on new technologies and the nefarious tactics of foreign bad actors, we risk losing sight at the use of deceptive campaign tactics used by our own politicians through more traditional approaches.

A total of £5.9bn was spent on political adverts during the 2019 General Election alone including, but not limited to, political parties. Although a shift to digital political campaigning became apparent in the 2017 election when spend on political leaflets declined for the first time in over fifteen years, it was still the case then that three times more was spent on leaflets than on social media adverts.

Based on the volume of leaflets dropping through letterboxes up and down the country since the current election was called, a similar pattern may still hold true – leaflets are still seen as an effective way to target voters. Unfortunately, they are also seen as an effective way to deceive them.

In 2019, a study by The Coalition for Reform in Political Advertising reported over 30 examples of political campaign materials that were indecent, dishonest, or untruthful. In an increasingly competitive political landscape where sometimes just a handful of votes can make a significant difference, parties of all colours are guilty of seeking to manipulate public opinion while being careful to just stay on the right side of the law.

Last year, the Conservative Party faced accusations from the press regulator, Impress, of “misleading voters” by publishing newspapers named after defunct titles to promote their policies in areas with by-elections. Earlier this year, in the London Mayoral elections, leaflets that were designed to look like a penalty charge notice also contained false information about an opponent were reported to the Crown Prosecution Service on the suspicion they breached electoral law. Such tactics only serve to contribute to the erosion of trust in our political system and compromise the integrity of elections.

In the lead-up to the general election, the integrity of political campaigning is under scrutiny. The fine line between innovative strategies that attract voters and deceptive tactics that distort reality is becoming increasingly blurred. The question political campaigners need to ask themselves is whether the short-term election gains of deceptive campaigning are worth the long-term damage these approaches have on public trust in politics and democracy. When people lose trust in our political institutions, they turn elsewhere. There is a reason voter turnout has been falling.

The CIPR is currently campaigning for the law to change so that organisations are required to be more transparent about their legitimate attempts to lobby the government. We have been encouraged at how this has been welcomed throughout the business world. As trust in business has fallen over the years, organisations now recognise the need to rebuild that relationship with partners and the public that includes a level of transparency about their political engagement. Political parties should take note.

Rishi Sunak stood on the steps of Downing Street when he became Prime Minister and promised to govern with “integrity, professionalism and accountability at every level”. He might be leaving Number 10 soon but, in the weeks in between, all parties should consider how they conduct their campaigns to uphold these values.

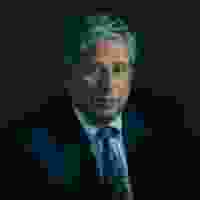

Alastair McCapra is the CEO of the Chartered Institute of Public Relations.