The problem is: choice

Patrick Timms highlights a view that has constrained free markets, and free societies, for so long.

For any true supporter of freedom, choice must surely be the most sacred of doctrines. It underpins every principle that holds free markets together, and we know that free markets and free societies create and support one another. As Milton Friedman noted: "A society that puts equality before freedom will get neither. A society that puts freedom before equality will get a high degree of both."

We know that when we give people both the means to succeed, and the hope to do so, they tend to grasp them with fervour. We do this best by giving them true choices, encouraging them to be arbiters of their own destiny. But while Adam Smith did remark upon the 'self-interest' of "the butcher, the brewer or the baker" – and not without some wisdom – to my mind this is in fact what also brings us together in unity. Because we share a common purpose, we share a common understanding along with a common morality, and these things form part of the glue that binds a society together.

That morality is not, as critics might suggest, a form of greed; rather, we merely acknowledge our own self-interest and, in doing so, we tame and tailor it to help support our society by contributing to it in the best ways we can – because we choose to. What we get back from that should mirror what we put in.

It is for this reason that I believe Brexit will rejuvenate that spirit once again within these islands. The European Union, at least in its upper echelons, has a fundamental culture problem with both Unity and Choice, in that it understands neither. The main trouble with the level of homogeneity behind the principle of 'ever closer union' is that it implies two things: –

1) 'Unity by uniformity' – how can we fail to be united if we are all the same?

2) 'Unity by necessity' – the EU is essential to all our economies, so how could anyone ever leave?

But neither of these principles can lead to true unity. Unity means mutual collaboration, in the face of difference and diversity, through choice. There must be a genuine choice as to whether to unite with others in a common purpose. The only tool the EU seems able to wield to manage diversity, however, is to eliminate it. The only way it feels it can hold its members together is to withhold from them a number of very real choices about their future as a nation – as the German Chancellor is rumoured to have all but confirmed at an event for the Konrad Adenauer Foundation in November 2018[1].

That is not Union – that is Dominion. It is also the way in which very corrupt people have always come to power, and retained it, throughout the ages – at least when they could not do so by the sword. Once, in Europe, it was said that "all roads lead to Rome". Now, it would seem, "all roads lead to Brussels". There has been a certain sense of inevitability about it, which fuelled the genuine culture shock felt by many people, both in this country and abroad, when Britain rejected that dogma – for a dogma it is.

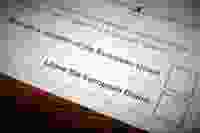

During the 2016 referendum campaign, people up and down the country were asking themselves many important questions, stemming from the perceived key issues of choice and control over our own lives. In the debate this became: "what will it mean for our lives if we stay?" and "what will it mean if we go?" But for me, as the campaign wore on, it became clear that the real nub of the matter was in fact something far more fundamental, and inextricably connected to the nature of choice: "what does it mean if we can't leave the European Union?"

We were certainly told by enough people that we couldn't – from the government, to the banks, to the majority of economists and academics who came scurrying out of the woodwork. True, the message was framed as 'shouldn't', but in fact the meaning behind it all was quite clear. Even the former President of the United States was wheeled out to warn us that free trade with a sovereign, independent Britain was of little interest to his country (a notion that his successor, whatever else you may think of him, has since emphatically denied).

There could be no viable alternative to remaining within this political and economic union that would not devastate our country, we were told. What all these negative campaigners did not appear to comprehend was that they were attempting to deny the British public the very soul of choice: each option presented must be genuine, and all opinions in the debate must be respected.

To put it in free market terms, the European Union has claimed a monopoly over the notions of unity and progress. It dominates that 'market' within Europe, denying free choice to those who might seek it in different ways. In an economic sense, it lauds the Single Market it has created as its crowning achievement, but alas this is indeed the 'single' market that its members are allowed to trade in freely, unless 27 other countries can collectively agree a deal with another.

In a political sense, it has established a supreme role for its legislature and its courts above those of whom it claims to unite, while convincing countless millions that only this approach can guarantee their 'rights'. And it has done these things for the same basic reason underpinning all monopolies: to protect itself from choices that might lead to competition, while simultaneously claiming to promote them. As the protagonist in the Matrix film series finally realises about the system designed to constrain and control him: "the problem is choice".

At its heart, this is a question of power, but not so much in the legislative or judicial sense: rather, it is the power over hearts and minds. This is the power that has caused millions to believe the European Union is vital to their values and their way of life. It is the power that led so many citizens of a highly developed, first-world society to believe they needed to be 'saved' from their own government by political structures set up beyond our borders. It is the power that caused Gina Miller to feel 'physically sick' – or so she said – at the referendum result. And it is the power that inspired Steve Bray to put his entire professional life on hold to campaign tirelessly against the legitimate result of the largest democratic exercise in British history.

Now that, dear reader, is true power. It is also why the question of just how 'democratic' the EU's political structures are is utterly irrelevant. By all accounts, there is plenty to say about that too – an elected Parliament that can merely amend legislation proposed by an appointed Commission would arguably resemble our system of the Commons and the Lords turned on its head – but I must admit, when I am asked about how democratic the EU is, I tend to reply: "that hardly matters".

I suggest that those who wrangle interminably about whether or not the EU's decision-making processes are founded upon democratic principles are rather missing the point. When you wield the kind of power that causes hundreds of millions to believe you are "the Way, the Truth and the Life" [John 14:6], then you have truly forged for yourself a Monopoly of the Spirit. From a Christian perspective, this may well be appropriate for God, but nothing of mankind born should hold such great sway over hearts and minds, for this denies us alternatives. Such a worldview can only invite hegemony, as indeed we have seen with the European Union.

All of this must surely run counter to the instincts and intuitions of anyone who supports free markets, but opposes sprawling monopolies. Markets have been dominated before by great entities that were deemed 'too big to fail', although history shows us that did not always save them in the end. But certainly during those periods of dominance, it was the consumers – perhaps, in this case, we might call them 'citizens' – who suffered the most.

With Brexit, we would seek to send a message, not just to our own country, nor even to the rest of Europe, but in fact to the entire world: "there is another way". We must not allow the core values that we say we all share – peace, freedom, democracy – to become monopolised by any single player in that 'market'. Nor should we allow ourselves to believe that the great abuses of the last century – hatred, warfare, empire-building – can only be prevented in the future through membership of a political union that seeks ever greater dominance in all affairs.

For that would make a caricature of the progress that all of humanity has made since the Second World War. We must demonstrate instead that peace and prosperity arise from human choice; that mutual collaboration must be a genuine choice; and that a stronger whole is brought about through embracing and overcoming enduring differences, which the principle of 'ever closer union' does not really allow for. Above all, we must show the world that these choices can be made without leading to 'political suicide' or 'economic collapse'. Brexit will be the first – and by no means the last – step on that long journey.

To put it somewhat poetically, Britain has a long history of writing its own future. It has shaped that narrative down the centuries through its own choices as a nation. I would prefer to live in a world where the choices around free trade, migration and sovereignty in the 'market' of any given nation state are made democratically by its 'consumers' – its own citizens. The combined decades of successful application of free market principles in countries around the globe have taught us that this is the best way to achieve peace and prosperity for all. For that, there must be a unity of purpose that is freely entered into. And for that, there must be choice.