The internet war begins

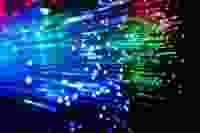

Recent reforms in the US to re-classify the internet as an information service allow companies to monetize the flow of information over the internet. Such a move undermines one of its central tenets of the internet, says Glenn Houlihan.

In the hyper-partisan political arena of contemporary America, few issues have inspired federal circumventing local legislation as effectively as the net neutrality debate. Across the country, states are taking what historically has been a national issue into their own hands, developing, and passing, laws designed to negate the Federal Communications Commission's contested reform.

On December 14 2017, the FCC, led by Chairman Ajit Pai, voted to repeal Obama era regulations – the Open Internet Order – which classified the internet as a public utility. Put simply, this ensured the internet remained free and fair; telecommunications companies were prevented from offering differently priced packages that prioritised or neglected specific sites.

However, the repeal, which re-classified the internet as an information service, effectively allows these companies to introduce such plans, in effect monetizing the very process of using the internet. It's worth noting the consequences can extend beyond commodifying certain sectors of the internet, as sites that providers don't like can be 'throttled', or blocked. This empowers telecommunication companies to broaden the scale and scope of both pricing structures (see Portuguese wireless carrier Meo's plan for a tangibly grim example) and traffic prioritisation. The knock-on effect this will have on consumers cannot be understated. Poorer customers may be unable to afford premium packages and therefore lose the ability to communicate with friends and family. Furthermore, this implicitly allows internet service providers to 'tier' traffic and obstruct specific sites and competitors.

Net neutrality has become a rare unifying issue for Democrats and Republicans. It was under the George W. Bush administration in 2005 that the FCC initially adopted rules resembling net neutrality, with the commission referring to the internet – in classically conservative terms – as an "engine for productivity growth and cost savings". A survey conducted by the Program for Public Consultation at the University of Maryland in March shows that 86% of American citizens support net neutrality. While it will come as no surprise that 90% of Democrats surveyed back reinstating the Open Internet Order, a resounding 82% of Republicans also support the measure – up 7% from December 2017.

Although AT&T and Verizon were quick to pledge their support for an open internet, these declarations were met with widespread derision from the online community. If indeed, "the internet will continue to work tomorrow just as it always has", as AT&T claimed, why did USTelecom CEO Jonathan Spalter promise to "aggressively challenge state or municipal attempts to fracture the federal regulatory structure that made all this progress possible"?

Before assessing the validity of local legislation, it is essential to deconstruct the role of Congress in the net neutrality debate. Massachusetts Senator Ed Markey has been a vocal proponent of reinstating the Open Internet Order – or a variation thereof – and, in February 2018, introduced a CRA (Congressional Review Act) to the Senate. In a 52–47 vote on May 16th, Senators voted to overturn the Federal Communication Commission's decision: all 49 Democrats voted in favour, with the support of Republican Senators Susan Collins, Lisa Murkowski and John Kennedy.

Although passing the Senate, the act wasn't expected to prevail in the long term. It lacks the required support – to even force a vote – in the house, and, were it to pass Congress, would likely be strangled by President Trump's veto. Nonetheless, its symbolism was formidable. Successful legislation could and would be passed, but it would have to come from the state level.

In the immediate aftermath of the repeal, Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey and former New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman announced they were filing a multi-state lawsuit against the Federal Communications Commission, alleging the FFC "completely failed to justify this decision". At the time of writing, over twenty other Attorney Generals had either signed up to the lawsuit or begun similar judicial proceedings.

In February, Vermont Governor Phil Scott became the fifth Governor to issue an executive order mandating that any internet service provider (ISP) holding or seeking a state contract must include net neutrality projections across all services. This vital demonstration of regional strength was followed by the 'Mayors for Net Neutrality' coalition, spearheaded by New York City Mayor Bill De Blasio. Late this April, one hundred Mayors signed a pledge to boycott ISPs that commit net neutrality violations. Here, we see a multifaceted structure of consumer protections: where the federal government fails the states step in, where the state fails the cities step up.

Yet it would be wrong to overlook the vital work happening in State Houses across the country. Here is where states can implement legislative change; change that stands the best chance of withstanding inevitable retaliatory lawsuits from ISPs. Three states have become torchbearers for protecting net neutrality: Oregon, Washington State, and, as of this week, California.

In February this year Washington became the first state to sign net neutrality protections into law (the legislation comes into timely effect on June 6) while Oregon swiftly followed suit in April. If the Golden State's legislation, bill S.B. 822, passes the state assembly, the entire West Coast will symbolise a rejection of the FCC's myopic judgement.

In doing so, they resolutely assert the right for states to challenge ill-considered, widely unpopular federal rulings; setting a precedent which threatens to erode the very authority of the Trump administration.