The Art of Feud

An occasionally serious look at the nature, structure and logic of "the feud": with examples from sport, philosophy and politics.

England's win against New Zealand in the final of the cricket World Cup was awesome, not least because it facilitated further gloating over the defeat of Australia of a few days before. Unlikely I know but if any of you have an email address for David Warner could you please drop him a message of consolation: " cheer up, at least you guys lost to the eventual winner"? I'm sure he'd appreciate it, he's a gentleman.

England v Australia: the paradigmatic sporting feud, a decades long tale of mutual antagonism. Every few years the English gracefully offer the Australians a chance to forget about their stuttering cultural development, and in return our Antipodean friends gracelessly seize it.

Sporting feuds matter because sport matters and because feuds are structurally fascinating. Sport matters because it is a species of play and play is a high spiritual activity. In play we are reminded that there are some things that are worth doing purely for their own sake; and play affirms an indissoluble connection between being free and following rules. Freedom that is not structured is not a freedom that is worth having: hence Nietzsche's reference to the serious play of children.

And feuds, when conducted according to their proper grammar, can be useful vehicles for the elimination of resentment. When we feud with someone appropriately, we are offering a form of respect. The best feuds are the ones we work hard at so that, hopefully, they acquire an energy of their own and the original reason for the falling out becomes forgotten. Family feuds can be like that: sustained, intricate and -if done properly-eventually conducted for their own sake. That is why funerals can be dangerous: if we are not careful, we end up talking to someone we shouldn't be talking to, by accident – and the hard work must begin again.

They have their own logic, too. Feuds are transitive. If -hypothetically- Ted is "feuding" with Margaret but Margaret never thinks about Ted (perhaps she is too busy doing the job she "stole" from him, for example) then that is not a feud but a sulk. But they are not commutative: in standard logic if A implies B and B implies C then A implies C. But if (for example) Theresa is feuding with George and George is feuding with Michael it does not follow that Theresa is feuding with Michael (or at least not necessarily). Thus we see that the logic of the feud is infected by the contingencies of the human soul: yet one more demonstration that the mind is not reducible to an algorithm and that the siren voices of doom, warning us that machines will take over the world, are best ignored.

So much, then, for the "philosophy of the feud". More interestingly: are there philosophers who feud with other philosophers? Of course there are. The most frequently cited example, however, is not a good one. In 1946 at a meeting of the Cambridge Moral Sciences Society there was an infamous incident involving Ludwig Wittgenstein, Karl Popper and a fire poker. It is alleged that Wittgenstein threatened Popper (who was an invited speaker) with the poker before storming out of the room. Whatever the truth is here, this would not have amounted to a feud: the most we can argue for would be a flounce. The title of Popper's paper, incidentally, was "Are there Moral Rules?".

A slightly better example is more recent. Ted Honderich and Colin McGinn are philosophers of mind. Honderich has argued that the "problem of consciousness" is soluble; McGinn is famous for arguing that if it is soluble then humans lack the cognitive apparatus required to discover the solution. An extremely deep, consequential and exigent metaphysical question is in play here.

The two of them fell out over a disparaging reference the latter made regarding the former's girlfriend. The feud has been intense (which is good), sustained (which is excellent) and vitriolic (not so much – but a woman is involved so there you go). Unfortunately, it has gone off the boil a bit since McGinn ran into some unrelated Harvey Weinstein-shaped personal difficulties and needed to redirect his energies into finding a new job.

But what of political feuds? These can be complicated by the fact that the language of politics embeds certain hypocrisies, one being that you must pretend to like the people you work with, even though everybody knows you can't stand them. The feud which takes a political form therefore has the potential to be subtle, encoded and exquisite or – and this can happen if, for example, the parties to the feud just happen to live next door to each other and one of them is a lunatic- they can descend into farce.

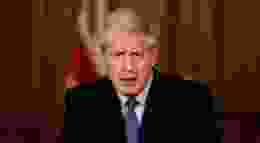

As I write this it is expected that Boris Johnson will become our next Prime Minister (by the time I finish he might be out of office – I'm struggling a bit, to be honest). The rumour is that he might be about to end his "psychodrama" (a Beth Rigby/Sky News word for feud) with Michael Gove and allow him to remain in his first Cabinet. Now I've no problem with Gove remaining in government – he is unintentionally hilarious- but let's hope the feud remains in place. When two people make up, and the etiquette of the feud ceases to apply, the subsequent relationship is invariably more awkward (I think we've all experienced this). If Johnson is going to insist that he's in the feud ending business, then he might do better to end the rift between the political class and the rest of us – before it escalates into something much nastier.

A final question: is it possible to feud with oneself? The current fad for "writing letters to one's former self" might be a basis for thinking so, especially if the former self is somehow able to reply. At the moment, perhaps the best we can say is that the technology is not yet available.

Speaking of former selves, there is an account of the Wittgenstein-Popper affair here. And if anyone is interested in how to start a musical feud, then you could do worse than kick off with advice from the Vinyl Mystic.