Punjabi ‘electables’ are no longer influential in Pakistani politics

With tension continuing to simmer in Pakistani politics following the ousting of Imran Khan as Prime Minister, Rai Mansoor Imtiaz Khan writes that whatever happens the days when select families, or 'electables' held sway over Pakistani politics are over.

The term 'electables' refer to landed, baradari (clan), and industrial elites who hold leverage in societies. Their enormous influence allows them to win substantial votes even without the backing of political parties. Punjab's electoral politics has been dominated for decades by a few families in every district. No matter which party they join during elections, their personal clout and family background pave the way for their entry into powerful corridors.

As a result of their considerable influence over the constituency, every political party prefers to allocate tickets to these figures rather than their ideological party workers, continuing in the 2018 general election. Imran Khan, who ran to challenge dynastic politics and change traditional Pakistani political patterns, also understood the importance of 'electables' before the 2018 elections:

"You contest elections to win. You do not contest elections to be a good boy. I want to win. I am fighting elections in Pakistan, not Europe. I have come to the conclusion that unless we took people in the party who know the art of winning elections, we would not be able to succeed."

Khan welcomed electables and awarded tickets to these influential political figures in several constituencies across Punjab.

Because of electables' powerful positions, party politics could not develop in the country. We need to look at the historical context of Punjab in order to understand why this elite-based politics is so strong there.

Landed elites played a key role under the British Raj in Punjab, often leading on key administrative duties and dealing with potential threats owing to their social status. Upon the introduction of provincial elections in British India, religious elites, who were major landowners at the time, backed the new Unionist Party led by Fazil-i-Husain, helping the party to dominate against other groups such as the Indian Congress and the Muslim League until legislative assembly elections in 1937.

Colonial Raj ended in 1947, but elite-based politics continued to dominate the country's political landscape. League's dependency on influential Punjabi landed elites posed fundamental challenges to the democratic political culture in the country. Because of their influence over economic resources, the landed aristocracy always converted labour's economic dependence into political support during the times of elections.

Ayub Khan (President from 1958 to 1969) pushed for rural middle classes to participate in politics and challenge the monopoly of powerful elite. However, he had to recognise the importance of the Punjabi elites and their influence over society; therefore, most of his basic democrats from Punjab were landed aristocrats.

Later presidents had different stances on these elites. Zulfikar Bhutto (father of Pakistani political icon Benazir Bhutto) stood up against elites and swept the 1970 election on the back of his slogan "Roti-Kapra-Makkan" (Bread, Cloth, House).

After toppling a democratically elected government in 1977, Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq abolished all actions taken by the predecessor against the landed aristocracy, in return for their support of his dictatorship. When General Pervez Musharraf overthrew Nawaz Sharif's government in 1999, his illegitimate regime was also supported by a mixed bag of landlords, baradari elites and industrialists from Punjab.

Rise of political charisma and decline of electables' influence in Punjab

A charismatic leader 'burns the fire' and awakens his or her followers about society's social and political issues. It does not matter whether a leader is moral or immoral, just or not, good or bad; political crises give birth to charisma. Incessant military involvement in politics, blatant corruption and lousy governance have created the crisis in Pakistan, which made Imran Khan a charismatic leader.

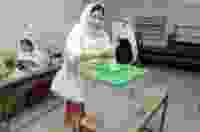

In the 2018 general elections, despite Khan choosing electables over his PTI party's ideological workers, it is pretty evident that most people voted for Khan and his political charisma. Many people I met during my MRes research in south Punjab said they voted for "Tabdeeli" (change). During my visit to the city of Dera Gazi Khan, many people said they had never heard of Zartaj Gul (the PTI candidate). In fact, most met her for the first time during the election campaign, yet they voted for her to support Imran Khan.

Landed and biradari elites were less influential in the 2018 elections. Influential political figures who weren't awarded party tickets by mainstream parties like PML-N (Pakistan Muslim League) and PTI did not dare run for election as independents. Despite their strong family backgrounds, they knew they would not be able to attract voters without a party ticket. This shows that even rural voters were intensely concerned with party politics.

For instance, in my electoral constituency of Jaranwala, Bega (of the Kharal clan) is the most influential family, seeing political involvement in some form from 1920 through until 2018. In 2018, no one from the family received a party ticket from either mainstream political party (PTI or PML-N). Even though their political legacy portrays them as the old guard in Punjabi electoral politics, it was pretty evident that they were not able to accrue votes without the support of the top political parties. There are several examples throughout the region where political parties did not award tickets to such powerful families. As a result, these powerful elites were either defeated or did not stand for election.

Khan's ouster from the premiership, Shehbaz Sharif, has ended up galvanising Khan's followers and boosting his political charisma even further. He has managed to convince his supporters that the US plotted his removal in response to his close ties with Russia and his "absolutely-not" narrative to Washington. Many of Khan's supporters, who view Khan's removal as an unceremonious, orchestrated act, repeat his words on social media.

The ongoing political debate at the street level reflects that Khan is not concerned about constituency politics. He believes that voters will vote for his charisma directly, whereas local elites have little influence over voting decisions. It seems that he does not need to rely on the old guard to win, even in rural constituencies. As Khan has said on numerous occasions, party tickets will be given to workers who have ideological ties to the party rather than the traditional political elites he chose during the 2018 elections.

Electables who betrayed Khan seem to be in deep trouble. It is becoming increasingly difficult for the old guards – who had openly expressed their discontent with Imran Khan and his policies – to walk on the streets freely and without fear. PTI voters are angry at their role in Khan's ousting.

Imran Khan has mastered the art of attracting large crowds. Nearly all major cities of Punjab have seen him in action. Khan's popularity and the acceptance of his ready-made narrative of "foreign conspiracy" among voters apparently show that Khan's political charisma is capable enough to muster enough grassroots support to contest the elections even without electables. It is time for Khan to make way for a new generation of politicians guided by ideology rather than by purely political expediency. His movement for freedom over thraldom can only be genuine if he defies the military's hegemony rather than just simply taking on his opponent.