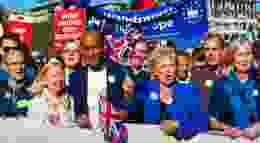

May taking Conservatives into 10 years of political oblivion

The parliamentary Conservative Party is putting loyalty to a blatantly inadequate leader over its electoral prospects. History suggests that this choice will lead to political oblivion for at least a decade.

You've got two ways to interpret the strategy behind Monday's budget: this government is increasing spending and cutting taxes either for an early election in 2019 or to blackmail Conservative Members of Parliament into accepting Theresa May's fake Brexit (lest Philip Hammond returns to austerity in order to pay for a no-deal Brexit, for which the electorate would punish Tory MPs with slimmer majorities than his).

I am betting the budget was meant to blackmail Conservatives into her fake Brexit. The day after, Theresa May ruled out an early election (although she hadn't kept that promise in 2017). More importantly, I doubt her partisans would be willing to chance a repeat of the mess she made of it in 2017. A general election isn't necessary until May 2022.

The real choice for Conservative political representatives is whether to stick for another three years with May, her fake Brexit, and Hammond's refusal to prepare for anything else.

History suggests that sticking with this blatantly misguided and deceptive administration would leave the Conservative Party unelectable for at least a decade. Whatever good coincides with the final years of the May administration, it would deserve no credit. Meanwhile, it would be deservedly blamed for years of stupid policies, indecisiveness, and broken promises. Conservative MPs would be deservedly blamed for sticking with her.

The easiest historical analogies are Neville Chamberlain and John Major, each of whose administrations was followed by at least ten years without Conservative government.

Before you think I am cherry picking, let's consider all nine previous Conservative premiers, stretching back more than eighty years. Theresa May combines the worst of each: Neville Chamberlain's introverted misguidedness, Winston Churchill's micro-managing, Anthony Eden's deceptiveness, Harold Macmillan's shiftiness, Alec Douglas-Home's unwillingness to learn, Ted Heath's aping of the socialist opposition, Margaret Thatcher's withdrawal, John Major's preoccupation with defaming critics, and David Cameron's shape-shifting to suit the polls. I can't say that May exhibits the best of any of them.

Now let's return to the first of them: Neville Chamberlain, with whom May has been compared before (I did so on these pages in January).

Don't let the conventional condemnation stop at his foreign and defence policies – which encouraged foreign aggression, and left Britain unready to defend itself or its allies.

The conventional history turns a blind eye to his effect on the Conservative Party, which did not win a general election between 1935 and 1950, then inherited a nation transformed with socialist institutions.

Chamberlain led from 1937 to 1940, latterly even after his foreign policies had clearly failed to prevent the Second World War, even after his long-war strategy was clearly strengthening not weakening Britain's enemies.

The government that succeeded Chamberlain was not a Conservative government – it was a coalition, in which socialists were predominant and dominant, who used the time to spin the policies and myths that won them a land-slide in 1945.

Winston Churchill led that coalition, but he was a fringe member of the Conservative Party, a defective Liberal, a stop-gap, who could not form a government without the opposition. He weakened his own party further by sending potential challengers into positions abroad, or thankless portfolios, or secondment to socialist heavyweights, while he surrounded himself with talentless appointees, and ran foreign and defence policies largely without Cabinet or Parliament. Sound familiar?

The electorate repudiated Churchill and the Conservative Party in unprecedented fashion when given the chance in 1945, ten years since their previous chance, when they had entrusted Stanley Baldwin with a large majority.

Like Chamberlain, May is appeasing continental European despots. She surrounds herself with yes-men and unqualified appointees. She keeps her Cabinet in the dark while she takes on personal diplomatic missions. She puts unelected party hacks and civil servants of her own fancy in charge of tasks that should be ministerial (such as negotiating Brexit). She clings to senseless and failed policies. She misleads Cabinet and the public about her intentions. She u-turns on her own promises and red-lines. She procrastinates, avoids, and misrepresents.

By design, her government is unprepared for anything except her fake Brexit. Her government has taken sovereignty over only 14 of the EU's 236 international treaties. It has not started trade negotiations outside the EU. It waited until this summer to lodge its proposal for taking back its sovereign seat at the WTO, so it is only now realizing that many self-interested sovereign members intend to block Britain's seat for years. Britons are facing their third new year since the referendum, with no Brexit except nominal separation in March 2019, followed by indefinite "transition," and a hustle into a fake Brexit after that.

May is as domestically stubborn and internationally submissive as Chamberlain. She micro-manages like Churchill, deceives like Eden, shifts her position like Macmillan. Like Douglas-Home, she can't learn from her mistakes. Like Ted Heath, she apes the Labour Party. Like Thatcher, she is too stubborn to give up personal policies. Like Major, she thinks a premiership is won by rubbishing critics rather than achieving anything.

John Major completes the analogies since Chamberlain. Each of Chamberlain, Churchill, Eden, Macmillan, Douglas-Home, Major, and May took the premiership without a general election, after the resignation of a premier, during a shady, unpopular, parliamentary party process.

True to form, John Major is fully committed to May's fake Brexit, and blames her fragility as a leader on her critics, just as he blamed his administration's instability on his critics. Like May's bare victory over Jeremy Corbyn in 2017, Major achieved his only general election victory in 1992 against a Labour Party leader (Neil Kinnock) that the electorate trusted even less, but Major couldn't repeat the stunt against Tony Blair in 1997.

Like John Major's administration in 1997, May's administration in 2022 would get no credit for any economic upturn, decline in crime, decline in immigration, or anything else, for the simple reason that those benefits would accrue despite the political administration, not because of it.

After Major, the Conservative Party was out of power for 13 years. Even then, it returned to only coalition government. If Conservatives don't get rid of May within months, they can bet on a similar outcome from 2022 until at least 2032.