Labour must not choke lobbying with red tape

Keir Starmer is on a mission to clean up British politics, but overhauling lobbying rules is not the way to do it. While recent scandals have sparked calls for change, the issue is more complex than what many make it out to be. If Labour pushes through these reforms, it won’t just impact the lobbying industry – it will stifle British businesses, weaken the public purse, and threaten British-led grassroots campaigns.

The lobbying industry gets a bad rap. Nearly 90% of lobbyists and PR executives have called for greater transparency in the sector, and this problem is made worse with lobbying scandals being normalised in government. A 2023 report, for instance, revealed over 170 former ministers and officials taking private sector roles linked to their past policy areas.

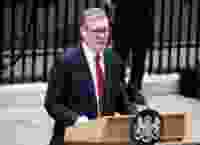

Starmer’s government seems eager to portray itself as the white knight in the crusade against cronyism and corruption. Supported by an army of 411 MPs, stamping out corruption has been a key election promise made by Labour that the British public want to see happen. As set out in its manifesto, a Labour government “will review and update post-government employment rules,” which includes “enforcing restrictions on ministers lobbying for companies they used to regulate.”

There are certainly a handful of individuals who abuse their positions for personal gain, but Labour’s proposed lobbying reforms are not the solution. Rather they risk doing more harm than good by restricting the valuable contributions former ministers can make to both businesses and the charity sector.

Former ministers offer invaluable expertise – a fact which these reforms overlook. Take George Osborne, for example, who served as editor of the Evening Standard after serving as chancellor. He advocated for tech startups, major infrastructure projects like Crossrail, and policies that boosted entrepreneurship nationwide. Restricting the employment prospects of former ministers like Osbourne means waving goodbye to the benefits they deliver after leaving office.

By wrapping red tape around a £2 billion industry, the government risks strangling the British economy and hurting the taxpayer’s wallet as a result. Whilst the government’s intentions may be well-founded, the economic impact of such reforms would be suffocating.

Implementing these reforms also poses practical challenges as lobbying possesses no set, clear definition. It spans from oral advocacy to expert consultancy, making clear regulation a bureaucratic nightmare and, consequently, these reforms unworkable. Labour’s proposed solution to this is to grant more investigative powers to the Independent Adviser on Ministerial Interests, but this simply will not work. Whilst there are clear cut cases of previous ministers lobbying, such as David Cameron, many don’t fall into this category. As such, the water is murky, and the government risks criminalising an entire profession.

Labour have also stumbled into the trap of failing to characterise the lobbying industry properly. Whilst many are quick to associate lobbying with large corporations, this could not be further from the truth. Individuals who ask their MPs to advocate for a local issue are, in fact, lobbyists. When Stonewall pressured the coalition government to legalise same-sex marriage they were, in fact, lobbyists. By shutting the door on ex-ministers working with large firms, the government also shuts out grassroots organisations who could benefit from ministerial expertise.

David Milliband perhaps best exemplifies this role. After leaving his post as foreign secretary in 2010, he turned to NGOs, instead of big business. He took the reins at the International Rescue Committee as president and CEO, and his leadership has been instrumental in delivering aid to refugees and displaced persons worldwide. His work, like Osborne’s, underscores the benefits that ministers and their expertise can bring to the world after leaving government. To pass these reforms, Labour would have to throw David Milliband’s work in the bin, and nobody wants that.

Labour’s lobbying reform proposals have done their job in providing the party with an electoral boost that helped them secure power. But with the showbiz of the election behind us, this new government has a choice. By pursuing this reform, British businesses will suffer and our position on the global economic stage will be weakened. Alternatively, the bill could be shelved. Businesses will prosper and receive expert advice from an array of ministers, which will help secure Britain’s place as a leading economic power.

Oliver Dean is a political commentator with Young Voices UK. He studies History and Politics at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) where he is the Treasurer of the LSE Hayek Society.