International law fully justifies the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill

Far from standing in the way of the Government's Northern Ireland Protocol Bill, international law sets out clear reasons why the Government must oppose how Brexit is being applied to Northern Ireland by the EU, writes Dan Boucher.

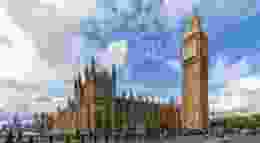

This week the Government introduced its long-awaited Northern Ireland Protocol Bill to address the significant problems associated with the way in which Brexit has been applied in the region. Rather predictably, in some quarters this has given rise to the serious accusation that the Bill asks Parliament to turn its back on international law. There are, however, a number of problems with this assertion, one of the most interesting of which actually comes from international law itself, specifically as it relates to the right to political participation.

The right to political participation can be found in provisions like Article 25 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and Article 21 of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights. The latter states:

'Everyone has the right to take part in the government of his country, directly or through freely chosen representatives. Everyone has the right of equal access to public service in his country.'

In the first instance, Northern Irish Brexit arrangements are inconsistent with our obligations under both Conventions in that they effectively deprive people in Northern Ireland of a significant element of what was their right 'to take part in the government of [their] country directly or through freely chosen representatives' until the end of 2020. Since January 2021 this right has been, uniquely within the UK, only applied to some of their government. The people of Northern Ireland have lost their ability to take part in the government of their country in relation to some 300 areas of law. They can no longer stand for election to become legislators making laws in these areas or elect a legislator to represent them in this task because, under the Brexit arrangements, these laws are now made for Northern Ireland by the EU, a polity of which it is not a part and in whose Parliament it consequently has no representation.

In the second instance, the Northern Irish Brexit arrangements fail in relation to the right to equal access to public service within a country. I can stand for election in the part of the UK where I currently reside to be a legislator, in relation to any of the different tiers of government that collectively make all the laws to which I am subject. However, when I move to Northern Ireland, I will no longer be able to stand for election to become a legislator making laws to which I am subject in some 300 areas. The result is that people no longer enjoy a right of equal access to public service in UK. One would expect that this unique public service regression will become a big issue for some people contemplating standing in the next General Election in Northern Ireland.

Of course, provision is made for the Northern Ireland Assembly to consent to the Protocol arrangement, and therein its laws. However, this will be up to four years after laws have been passed and rather than providing the opportunity for MLAs to take part in the making of the legislation, they will have to make do with effectively accepting or rejecting a potentially large body of legislation across disparate areas in relation to which they will have no ability to say yes to some laws and no to others.

Moreover, even if the Assembly voted against, this would not have the effect of causing the laws to immediately cease having effect in Northern Ireland. It would rather necessitate more UK Government negotiation with the EU. Thus, quite apart from denying the people's representatives a role in the making of the legislation to which they are subject, this arrangement is in, any event, absurdly blunt and does not even result in the legislation automatically falling away in the event of a no vote. Such is the debasement of the right to participate in the Government of one's country in this arrangement that it degenerates and disintegrates into farce. It is hard to imagine a more demeaning and humiliating arrangement.

We confront the right to political participation in international law at a Northern Ireland-specific level by turning to the Good Friday Agreement (GFA) and the right that it affords the people of Northern Ireland 'to pursue democratically national and political aspirations.' In doing so it is important to recognise two things. First, this is an additional Northern Ireland-specific right that has not been formalised elsewhere. Second, this provision was and is completely central to the GFA, which involved persuading people to turn away from violence and to invest their focus exclusively on seeking change through democratic means. Democratic rights are, therefore, particularly important in Northern Ireland.

Prior to Brexit, people in Northern Ireland were able to pursue democratic objectives as they related to all the directly enforceable laws to which they are subject. They could stand for election to become a legislator, making those laws for their community, or they could select their preferred candidate to become the legislator. The impact of Brexit arrangements in Northern Ireland, however, was that on 1 January 2021 the people of Northern Ireland lost this democratic avenue of expression in relation to more than 300 areas of law.

Moreover, in the case of the GFA, there is the additional international constraint arising from a foundational provision of the Protocol, Article 2, which specifically obliges the UK Government to ensure that there is no diminishment of any GFA right following Brexit. Article 2 (1) states: 'The United Kingdom shall ensure that no diminution of rights, safeguards or equality of opportunity, as set out in that part of the 1998 Agreement entitled Rights, Safeguards and Equality of Opportunity results from its withdrawal from the Union…'

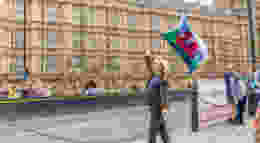

Given that the right of people in Northern Ireland to pursue democratic objectives in numerous areas of law has been taken from them, it is plain that Northern Ireland has experienced a radical diminishment of her GFA rights since Brexit. When one has regard for this failing in the wider context of an appreciation of Northern Ireland's history, and of the great achievement of the GFA in persuading people to democratic over violent action, it is staggering that the EU thought it appropriate to propose an arrangement that selected Northern Ireland as the place uniquely in the UK where ballot box engagement should be devalued.

Moreover, and of huge importance, the GFA's democratic rights are not just protected by two international legal instruments, the Agreement defining the right and the Protocol requiring that there be no diminution of the right post Brexit. These international obligations that are actually made directly available in domestic law, courtesy of the Withdrawal Agreement Act. They exist today and, very properly, the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill not only maintains them but also prevents any minister from amending them.

In this context we must be very careful about suggesting that those pressing for changes in the post-Brexit Northern Ireland regime have no concern for international law and that anyone having concern for international law must oppose the Bill. Indeed, when one considers the international legal obligations that necessitate far-reaching change to the Protocol in terms of political participation mindful of the Troubles and the GFA, the current approach becomes absurd such that it quickly becomes plain that far-reaching change is not only right but also urgent. If the EU wants to start a trade war with the UK because we refuse to turn our backs on our human rights obligations, they can, but it won't end well for them.

Dr Dan Boucher is a former member of the Conservative Party and Conservative Parliamentary candidate in Wales. He left the Party over the Protocol and moved to Northern Ireland where he now works as Senior Researcher to Jim Allister, the MP for North Antrim and Leader of the TUV.