Indeterminate sentences are an injustice to all

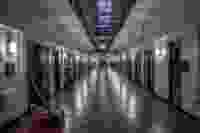

The UK's prison system is broken. Despite its abolition in 2012, prisoners serving an IPP sentence are left in prison with no defined date of release. This is having detrimental consequences across Britain, it needs to be scrapped in totality, writes Noel Yaxley.

In 2006, James Ward was convicted for an assault charge and was jailed for 22 months. A usual sentence for such a crime. He was told he had to serve a minimum of 10 months. But he wasn't released until 2017. So why did he end up serving 11 years instead? James suffered from mental health problems and as such was unable to cope with prison life. In protest, he set fire to his mattress and was re-sentenced – being given an Indeterminate Sentence for Public Protection (IPP) for Arson.

There will be a lot of people who are unaware of an IPP sentence. Under section 225 of the Criminal Justice Act 2003, IPP's were brought in by then Home Secretary David Blunkett and were intended to shield the public against criminals whose crimes were not deemed serious enough to warrant a life sentence but were too dangerous to be released when their original sentence had expired. These are a form of indeterminate sentence where offenders are given a minimum jail sentence (tariff) but no maximum one. The release date is purely left to the discretion of the parole board. So in effect these prisoners serve a sentence with no defined end date.

Despite being abolished in 2012 after Strasbourg's European Court of Human Rights labelled them 'arbitrary and unlawful', IPP's are not retrospective, meaning that those prisoners serving an IPP sentence are left in prison with no defined date of release. Ministry Of Justice figures from June 2020 show that 3,328 prisoners in England and Wales are still serving an IPP sentence: 93 per cent of whom have been locked up beyond their original sentence.

IPP sentences came into force in 2005 and were specifically meant for the worst type of person: sex offenders and extremely violent people like terrorists who would do untold damage to society. 900 were estimated to be incarcerated under this sentence, but over 8000 IPP sentences were imposed. Those who committed low-level crimes of less than two years, 358 are incarcerated on the sentence. Almost half of these (187 people) have been in prison for more than ten years after their original tariff expired.

Seen as a less severe alternative to a life sentence, a judge could hand down an IPP sentence if they felt the crime committed represented what the Criminal Justice Act 2003 calls a 'serious specified offence'. Something you would not normally attribute to a case of attempted robbery and possession of a weapon. I am referring to the case of Charlotte Nokes. Nokes was given an IPP in January 2008 and was given a fifteen month sentence. She was found dead in her cell in HMP Peterborough in July 2016: seven years over the minimum tariff.

Nokes' tragic case is not unusual. The Prison and Probation Ombudsman (PPO) investigated the deaths in prison of those serving IPP sentences. The report concluded that fifty four prisoners have suffered self inflicted deaths between the years of 2007-2018.

For those fortunate enough to be released by the parole board, it isn't over yet. As a released IPP prisoner you will remain on licence for ten years after which you can apply to the parole board to have it removed. Alongside this, as a precondition for licence a plethora of stipulations and regulations are attached limiting freedom of movement and association. You can be recalled at any point even if you do not commit a crime.

Those who are recalled are imprisoned without trial. In 2017 the Chief Executive of the Parole Board found sixty per cent of those recalled on IPP's broke their licence conditions and were not responsible for committing a further crime.

We need to do more to help those who are suffering under IPP sentences. Having effectively no release date these people will become lost in a heartless, bureaucratic system. As of writing the number of those released who served IPP's fell in the last two years: from 608 in 2018 to 346 in 2020: a 43 per cent drop.

With over 82,000 people locked up in England and Wales, we have one of the highest per capita prison populations in Western Europe. It doesn't help when you understand the number has effectively doubled in the last twenty five years. With 71 of our 116 prisons overcrowded this is a breeding ground for violence. These prisoners are at the mercy of prison gangs and with over 7,000 prison staff having left since 2010, these people are in a seriously dangerous environment. With so few staff it can surely come as no surprise that the PPO found one in five prisoners diagnosed with mental health problems were not treated. Leaving people to rot in prison with no help is not rehabilitation. It is illiberal.

Our prison system is a disgrace and these arbitrary Victorian sentences are a scathing indictment on our so called liberal western values of justice and human rights. If we really are a society that respects civil liberties, IPP sentences need to be scrapped immediately and in totality.