Higher paid MPs can benefit democracy

As part of a series of columns on our Parliamentary system as I step down at the next General Election, I reflect on some of the factors influencing the perceptions of colleagues and constituents alike. With some members currently under the media spotlight for various misdemeanours, it is perhaps easy to forget that the overwhelming number of people come into Parliament for the right reasons. Those who do not, or whose behaviour subsequently falls short, tend not to last the course, especially with the advent of recall procedures alongside changing social acceptance of misbehaviour. This is how it should be given institutions can only be as good as their people.

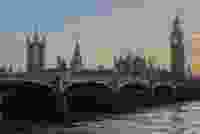

By any standard, international or otherwise, Britain has a clean political system. Standards in public life are high, with the Nolan Principles of selflessness, integrity, objectivity, accountability, openness, honesty and leadership enshrined across the public sector. When individuals do break these principles, there are consequences, and our robust free press also play an important role in exposing and policing these standards.

It was largely because our politics has generally been so clean – with some dishonourable exceptions over the years – that the expenses scandal came as such as shock. The wide-ranging and longer-lasting effects of this scandal were to cast a pall over MPs in the public’s eye as people who were enriching themselves by stealing from the taxpayer, even though the number of MPs who were actually convicted of genuine wrongdoing was immensely small.

The establishment of the Independent Parliamentary Standards Authority (IPSA) has meant that, since 2010, MPs have not set their own pay or pensions. This I support given I felt it was wrong and never voted when such votes came to the House. However, this is an interesting constitutional arrangement, since MPs through Parliament are the ultimate authority in the land and to a certain extent are the only individuals capable of taking such a decision. Yet, in order to bolster public confidence in the system, MPs have delegated responsibility to IPSA.

Despite this, MPs’ postbags would suggest that many of our constituents still believe and complain that we are regularly voting to increase our salaries by vast amounts. Indeed, a focus group some years ago suggested the costs of net zero could be covered by confiscating MPs’ salaries – indicating that people believe both that the costs of net zero are much smaller than they are, and that MPs are paid much more than they think. This is not helped by IPSA categorising all staff salaries and office expenditure as an MP’s expenses.

Whilst an MP’s salary is generous by any yardstick, anecdotal evidence suggests it may be insufficiently high to attract and retain good candidates, who may well be taking a significant pay cut to become an MP or who may be much younger, and therefore less financially established, than MPs a generation or so ago. Suggesting MPs should be paid more is never a popular or easy case to make, but it would be a relatively small cost overall and could lead to an even higher calibre of MPs at Westminster.

Meanwhile, a ban on second jobs, which is regularly mooted, is another matter causing concern for colleagues and constituents alike. This would further insulate the Commons from the outside world and the wealth of experience that legitimate outside interests often bring. In any case, any ban on second jobs would somehow have to square how being a Minister isn’t like having a second job – which to all intents and purposes, especially in time commitment and increased remuneration, it is.

Meanwhile, current events in Gaza, coupled with the murder of two colleagues within the last decade, highlight the threats that MPs now face in a way that never occurred to us when my cohort joined Parliament in 2001. Social media is a relatively new force with many advantages for politicians, not least in the direct and unmediated connexion it offers between MPs, constituents and others, but it is also allowing those with extremist views to reach a wider audience, which was not possible before.

The uncomfortable truth is that the abuse and threats MPs receive over social media, which can spill out into the real world, is certainly putting people off going into politics. People have always disagreed – this is the meat-and-drink of politics – but in recent years these disagreements have taken on an edge that did not exist when I entered Parliament. The situation is not helped by the language and behaviour of some politicians in the House.

The Government’s hands aren’t clean on this, but it is particularly dispiriting how Opposition Day debates have become ‘weaponised’ so the opposition can fire off press releases about how Conservatives have ‘voted in favour’ of pumping raw sewage into rivers, and the like. People outside Parliament, who sensibly and reasonably aren’t genned up on Parliamentary procedure, don’t pick up the nuances and we have a crop of furious constituents to respond to. No doubt these sorts of ‘dark arts’ turn people off politics, and of standing for election too.

As previously alluded to, MPs traditionally tended to be those who were well-established in their careers and the expectation was that, provided they were returned by voters, they would serve for a good stretch. This general rule is decaying, as people are increasingly entering Parliament much earlier, but increasingly are also leaving it earlier. This turnover is a shame, as it erodes the Commons’ store of institutional memory, as it can mean MPs are leaving the Commons just as they have learnt the ropes of the job.

The decreasing age of new MPs presents a further challenge in that fewer are entering Parliament with experience to bear. Backbenchers are better able to question Ministers if armed with a depth of understanding of the issues at hand – this assists Parliament’s questioning of the Government. Some colleagues do this successfully. Certainly, my travels through the Middle East as a young man, driving new Range Rovers and Peugeot 504s out to their owners who had bought them at source in Europe, together with my experience in the Army, informed my questioning of our interventions in the region from.

A new rule is developing that former senior ministers tend to depart the Commons, rather than stagging on as a backbencher – perhaps linked to the financial disclosures MPs are required to make and the close public scrutiny of these that follow. Historically it was quite common for MPs to serve in and out government over several decades, and in this sense the return of David Cameron, albeit via the Lords, is a throwback to historical norms. That the commentariat are sensing the injection of energy and heft at the FCDO of a former senior minister once again in the saddle should only be surprising in that it is thought of as novel.

MPs are rightly held to high standards, and those who criticise MPs’ behaviour seldom acknowledge that misbehaviour generally does not go unpunished – much more so than in the other assemblies in the UK. A robust standards committee and recall powers mean that wrongdoing tends to be punished, invariably with a by-election. Boris Johnson’s statements at the Despatch Box as Prime Minister set in motion a train of events which culminated in his resignation from the Commons, even before a recall petition was activated. The high number of by-elections in this Parliament can be seen as the system regulating itself, and therefore as a good thing. This should give confidence to prospective MPs.

Upright and high-calibre individuals should always be drawn to politics. I remain convinced that almost everyone comes into Parliament for the right reasons, but I have concerns at the decreasing age of both new MPs and those leaving the Commons voluntarily. The new Parliament will have to grapple with these issues, as will society in general – for instance, people may have to decide whether they want their MPs to act as ‘super-councillors’ or concentrate more on national matters. The problem of abuse and intimidation of MPs is replicated across public life, so will likewise require a national effort to resolve. All this is doable if the will is there.

John Baron is the former Conservative MP for Basildon and Billericay and a former Shadow Health Minister.