Stop Moldova's media ban to prevent more freedom of speech risks

Moldova’s democracy is moving in a dangerous direction. The country’s Commission for Exceptional Situations—given extraordinary executive powers due to the state of emergency called since the outbreak of the war in neighbouring Ukraine—first banned six television channels from operating in December 2022. This was followed by revoking the license of six more TV stations, while simultaneously blocking some 20 news websites in October 2023. Such anti-democratic action saw media NGOs, including the Centre for Independent Journalism, the Electronic Press Association, RISE Moldova and the Access-Info Centre expressing concern.

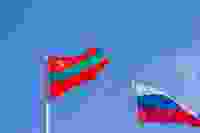

It must be remembered that Transnistria remains one of the great outstanding frozen situations following the collapse of the Soviet Union. This places additional pressure on the media landscape, and those concerned about the issue in Moldovan society have used this to justify the ban. Some in the Moldovan parliament are keen that the media does not make any comments that could be seen as provoking Russia into further action. Whatever the ostensible justification however, employing anti-democratic measures such as censoring the media through banning outlets and the government’s banning of political parties, is neither acceptable nor conducive to building a democratic future in this complex region.

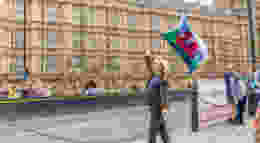

The government’s attack on Moldova’s free media landscape is already reason enough to be concerned, but the Commission’s banning of all of the Chance party’s candidates from participating in local elections on November 5, crossed a line. Freedom of expression has come under attack on multiple fronts in Moldova, already including broadcast and online media, and the most fundamental of political processes: Moldovans’ right to vote for their preferred candidates. Democratic regression must be immediately stopped and reversed before further freedoms of expression are threatened.

Government-imposed limitations on the media are not uncommon, but most often characteristic of authoritarian states that try to maintain close control over public opinion. This is a serious warning sign in established democracies, let alone in nascent examples. The banning of outlets signals the beginning of a process targeting freedom of expression at large, often leading to the ultimate monopolisation of determining what information counts as “facts”. Media outlets close to the government already echo their public narratives while Moldova’s advertising market is dominated by groups close to powerful politicians, to the detriment of independent media.

This process has already moved beyond mere bans in Moldova, where more than 120 recorded cases of threats and outright attacks against journalists and other media workers from 2020–22. In multiple instances, government officials and parliamentarians made these threats, although supporters of particular parties have also participated in the intimidation and cyber-harassment of journalists.

These are early symptoms of a deteriorating democracy. The freedom to criticise a government and vote that government out of power through free, fair and open competition between parties, are cornerstones of a democracy. Restricting the flow of and limiting political opinions are obvious means of solidifying a narrative and concentrating power.

The irony in Moldova’s recent limitations on the freedom of expression is that these were rolled out under the country’s allegedly liberal, pro-democratic and pro-EU Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS). President Maia Sandu staked her entire political career and re-election in 2024’s presidential elections on Moldovans’ support for the country’s EU membership. And while government officials tout Moldova’s close proximity to EU values, their actions show a very different reality.

The Venice Commission, a body of the Council of Europe, openly criticised Moldova’s decision to ban the Chance party, arguing that it did not fully respect the principle of proportionality. The Council of Europe encouraged Moldova to review the extensive rights of the Commission for Exceptional Situations, a sentiment that the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) also echoed.

EU membership in and of itself will not resolve the recent issues of democratic backsliding in Moldova but rather, could open the gateway to its solidification by providing tacit approval for such anti-democratic actions, whilst simultaneously receiving billions of Euros from the EU in development financing.

Europe should be aware of the warning signs and actively oppose this deconstruction of democracy. The country’s Commission for Exceptional Situations has enjoyed its unrestricted mandate for far longer than is justified. As Moldovans gear up for elections in autumn, legitimacy can only be guaranteed if the vote is open, free and fair. Reversing the controversial media ban and guaranteeing the protection of journalists and media workers from harassment and intimidation would be the appropriate first steps.

Neil Watson is a Eurasia expert, researcher, editor and a journalist. He is the CEO of the Aitmatov Academy.