After COP26, it’s time to admit our foreign aid approaches don’t work

Whilst rich nations have caused climate change, it is developing nations that will pay the price. Leaders in the developed have made noisy promises about financing the developing world's adaptation efforts against climate change. However, this fund still remains fatally underfunded after COP26, writes Mukhtar Karim.

There are no global courts or mechanisms to enforce the pledges made at COP 26, only the crumbling pillars of good will. Rich nations must now commit to spending their sparse commitments wisely if they want their funds to make a difference, and not just to become another box-ticking exercise.

Fragmented, 'siloed' foreign aid approaches don't work. Having one programme for food, another for water and another for education often solves none of the problems they're meant to. Instead, we need holistic, all-encompassing programmes that actually promote development, and don't just tick boxes.

An example of such a siloed foreign aid program can be seen in the Gyandoot program in India. The program provided computer kiosks in rural areas, yet the lack of electricity and connectivity meant that only a few of the kiosks proved commercially viable. The computers were left to fall into disrepair; today they nothing more than a symbol of international incompetence. This illustrates the flaws of a siloed approach; it fails to see the forest from the trees.

The UN Environment Programme estimates that developing countries need $70 billion per year for adaptation, yet a measly $356 million has been committed at the latest climate talks.

However, how we spend our foreign aid budgets can be more important than how much we have to spend. For example, the cost eradicating Smallpox, a disease that killed 300 million people since 1900, is estimated to have been $300 million. For context, this is the same cost as a Pirates of the Caribbean Movie, or the price of one day of war in Afghanistan. Small budgets can go a long way when the outcomes are transformative, the efforts to deliver them tenacious and the will of the collective invested in changing the destiny of the millions. .

Unfortunately, foreign aid programs, like that in the Gyandoot program in India, are often not spent this well.

There moral imperative for foreign aid funds is undeniable. In crisis situations like the Tsunami or Haiti, aid can buffer against immediate suffering; however, it is not a long-term solution, it only offers immediate relief.

In many cases, aid can breed dependency, which sometimes prevents any form of improvement in terms of human development and per capita income, and leaves communities devastated when the aid on which they have become dependent is withdrawn.

In the UK, a recent case in point is Boris Johnson's £4bn of cuts to the foreign aid budget which critics warn will cause significant suffering to some of the world's poorest people. This concern was echoed by the International Planned Parenthood Federation who launched a legal challenge to the cutbacks, citing the catastrophic impact they will have on millions of women, girls, and marginalized people worldwide, and the thousands of lives that will be lost in the process.

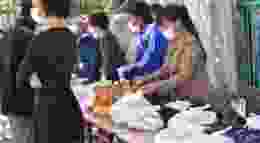

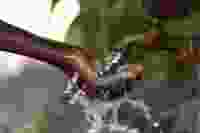

But there are alternatives to this fragmented and erratic forms of development aid; we need programs that seek to offer sustainable and holistic solutions to the world's humanitarian problems. One such example can be found on the island of Unguja, also known as Zanzibar Island, located just off the coast of Tanzania. The island is home to a population of 1.6 million people, many of whom do not have access to clean drinking water. This leads to poor health and unnecessary deaths from a lack of safe drinking water. In fact, the very process of collecting clean water means women and children globally lose 200 million productive hours each and every day.

So, on the island of Zanzibar, they have begun tackling this problem by trialing a pioneering water program that is guided by three principles; zero thirst, zero carbon emissions, and zero single-use plastic. The program uses solar power to extract, purify and distribute the water throughout the island. The installation of an island-wide grid also lowers costs and ensures access for all. Solar panels are installed on the roofs of schools so that while they form part of a strategic clean water solution, they also power laptops for teachers and students. School attendance rises and hospital admissions drop. As for the tourists, the carbon credits generated from the water project offset the carbon footprint they widened in order to get to the island.

This is the type of holistic thinking that needs to serve as a blueprint for the style of foreign aid we need. Ultimately, if foreign aid isn't working it needs to be reconstructed. It needs to be accountable and transparent from beginning to end. More importantly, we need to get the most out of every dollar, euro or pound spent. When funds are sparse, and time to act more limited than ever, the need to get it right is even more severe.

Having rich nations calling the shots on how to tackle climate change is like having the prisoners on death row decide on crime and justice policy. All we can hope is that the guilty finally step up to protect the innocent.