Britain halts populist advance

The UK is leading the fight against the populist advance that continues to blight the Western world, says Charlotte Kude.

Theresa May's decision to hold a General Election on June 8 took the country by surprise, including her own party. Ever since she became Prime Minister, she has repeatedly ruled out a snap election to instead focus on the process of exiting the EU. She soon realised that she would need to bring Westminster together behind her and just three weeks after triggering Article 50, decided to call an election.

She could have hardly chosen a more opportune time for her party, enjoying up to a 20-point lead in recent polls. More than a parliamentary majority, an entire country is about to unite behind the change of direction chosen during last year's referendum. Dozens of seats in the North of England where Conservatives hadn't won for decades, but that largely returned a Leave vote are predicted to turn blue. Contrary to all fearmongering about the United Kingdom breaking up, the Scottish National Party could lose as many as twelve MPs as voters reject independence.

The British electorate will be asked to make a major decision at the ballot box for the third year in a row. Contrary to most western democracies, voters are abandoning the fringes to rally to the centre. UKIP's approval ratings have either stalled or dropped in recent weeks. This shows that more democracy, not less, is the answer to current populist trends – and Britain is showing Europe, and the world, exactly how it's done.

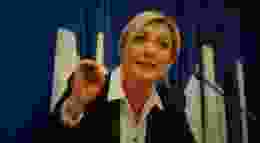

Never mind the arrogance of those who portray French presidential candidate Emmanuel Macron as the saviour of liberalism, ignoring that over three quarters of the French electorate didn't vote for him. Never mind that these same voters also put the National Front in second place and that Marine Le Pen's rating are at an all-time high. The centrist candidate may very well win the election on Sunday, but that doesn't change the fact that populism is on the rise in France, not declining.

Similarly, in the Netherlands, where despite losing the election on March 15, far-right leader Geert Wilders nevertheless managed to come out a strong second. Twenty Members of Parliament were elected on a protectionist, Eurosceptic and anti-Islam platform.

The forces behind French and Dutch nationalism have little in common with the outcry that prompted Britain's rejection of the EU via the ballot box. Pro-EU voices may find it convenient to amalgamate the two, which is precisely why populism is threatening their system in the first place. Instead of dismissing their people's concerns as populist, they should learn from Britain that only more democracy can sustainably appease tensions.