Solzhenitsyn’s ’78 Western society failings still dominate

Re-examining novelist, historian, and anti-Communist campaigner Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's 1978 Harvard University speech on the struggles facing Western society, Ken Crawford is struck by how many of the themes identified are no less relevant today. He believes this points to a deeper social challenge that crosses traditional party boundaries.

Solzhenitsyn's Harvard Speech (click here) of '78 Still Resonates. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was serving as an officer in the Red Army when he was arrested for criticising Stalin in a private letter and imprisoned. The Soviet prison system, the gulag, was already being used by Stalin as means through which to liquidate vast sections of the population, partly an exercise in ethnic cleansing, partly a political move to stifle opposition, partly an exercise in naked terror every bit as evil as the Nazis yet somehow without making the same impact on the western psyche.

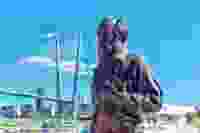

Solzhenitsyn spent years doing hard labour in the most hostile of conditions. He recounts his own experiences and those of people he encountered in the Gulag Archipelago, a book that was pivotal in destroying the credibility of Communism in the West. After serving his prison term Solzhenitsyn was deported to the West, where his fame grew. In 1978 he was awarded an honorary literary degree from Harvard University. He used the occasion to offer a critique of the West based on his experience of living there for a number of years and contrasting it with his experience under Stalin.

The original speech of '78 is quite long and not all of it still relevant, but there are some broad themes sketched out by an intelligent outsider, offering a critique of the West that still resonates four decades on. In my view these are the letter of the law, media power and loss of spiritualism.

1. The letter of the law

The limits of human rights and righteousness are determined by a system of laws. People in the West have acquired considerable skill in interpreting and manipulating law. Any conflict is solved according to the letter of the law and this is considered to be the supreme solution. If one is right from a legal point of view, nothing more is required. Everybody operates at the extreme limit of those legal frames.

A society based on the letter of the law and that never reaches any higher is taking very scarce advantage of the high level of human possibilities. The letter of the law is too cold and formal to have a beneficial influence on society. Whenever the tissue of life is woven of legalistic relations, there is an atmosphere of moral mediocrity, paralyzing man's noblest impulses.

The defence of individual rights has reached such extremes as to make society as a whole defenceless against certain individuals. It's time in the West to defend not so much human rights as human obligations.

2. Media Power & Bias

The Western media enjoys the widest freedom by global standards but the main concern is not to infringe the letter of the law. There is no true moral responsibility for deformation or disproportion. Because instant and credible information has to be given, it becomes necessary to resort to guesswork, rumours, and suppositions to fill in the voids. The media can both simulate public opinion and miseducate it. A person who works and leads a meaningful life does not need this excessive burdening flow of information. Hastiness and superficiality are the psychic disease of the 20th century and more than anywhere else this disease is reflected in the media.

The media has become the greatest power within Western countries, more powerful than legislative power, the executive, and the judiciary. They are unelected and not accountable to the public. In the communist East a journalist is appointed as a state official. But who has granted Western journalists their power and with what prerogatives? One gradually discovers a common trend of preferences within the Western media as a whole. Enormous freedom exists for the press, but not for the readership because media mostly develop stress and emphasis to those opinions which do not too openly contradict their own. This gives birth to strong mass prejudices, to blindness. It will only be broken by the pitiless crowbar of events.

3. Loss of spiritualism

The mistake must be at the root, at the prevailing Western view of the world which was first born during the Renaissance and found its political expression from the period of the Enlightenment. It became the basis for government and social science with man seen as the centre of everything that exists. We turned our backs upon the Spirit and embraced all that is material. This new way of thinking did not admit the existence of intrinsic evil in man nor did it see any higher task than the attainment of happiness on earth. All other human requirements and characteristics of a subtler and higher nature were left outside the area of attention of state and social systems, as if human life did not have any superior sense. A total liberation occurred from the moral heritage of Christian centuries with their great reserves of mercy and sacrifice. The West ended up by truly enforcing human rights but man's sense of responsibility to God and society grew dimmer and dimmer.

On the way from the Renaissance to our days we have enriched our experience, but we have lost the concept of a Supreme Complete Entity which used to restrain our passions and our irresponsibility. We have placed too much hope in political and social reforms, only to find out that we were being deprived of our most precious possession: our spiritual life. In the East, it is destroyed by the dealings and machinations of the ruling party. In the West, commercial interests suffocate it. This is the real crisis.

We have to rise to a new height of vision, to a new level of life where our physical nature will not be cursed as in the Middle Ages, but, even more importantly, our spiritual being will not be trampled upon as in the modern era. This ascension will be similar to climbing onto the next anthropologic stage. No one on earth has any other way left but upward.

Conclusion

I personally found it quite shocking that these themes were identifiable 40 years ago, believing them to have arisen around the time of Blair's Labour Government. That an outsider could see these things so far back points to a deeper social challenge that crosses traditional party boundaries. While non-traditional political parties are emerging in Europe, it is not obvious that any of them address these themes, assuming one believes them important to address. Perhaps it will require what Solzhenitsyn called the 'pitiless crowbar of events' to effect change. That said, perhaps there are options open to the individual. Laws are not lumps of stone immoveable and unyielding; they can be changed by determined individuals. The media landscape is fracturing with non-traditional online media on both the political left and right gaining traction. This is happening because individuals are making the choice to switch. Spirituality is, above all, something the individual can take on themselves if they wish and in a manner that befits them.